“But between a balanced republic and a democracy, the difference is like that between order and chaos.”

—John Marshall, Life of Washington (1805)

“At no time, at no place, in solemn convention assembled, through no chosen agents, have the American people ever proclaimed the United States to be a democracy.”

—Charles and Mary Beard, America in Midpassage (1939)

Republics and Democracies

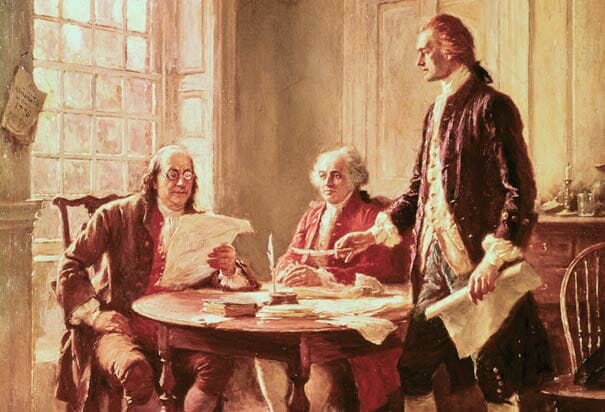

At the close of the Constitutional Convention, a Mrs. Powell of Philadelphia walked up to Dr. Franklin to get the inside scoop on what the Convention had finally produced. “Well, Doctor,” she asked, “what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?” Without a blink, Franklin replied, “A republic, if you can keep it.” A republic, he said. Not a democracy.

The word republic comes from two Latin words: res publica—literally, the “things public.” That doesn’t tell us much on the surface. It isn’t as descriptive as democracy, which means “the rule of the people.” But in the history of the West, and especially in political history … republics and the republican tradition have been associated with the way Rome governed itself for a period of time on the way to empire. The Roman republic operated in terms of political representation, and it assumed the existence of some moral and legal standards that every citizen was supposed to assume and acknowledge.

Democracies, on the other hand, have their prototypes in ancient Greece, particularly Athens, during those brief times when tyrants weren’t in charge. Democracies involve the direct political participation of all the citizens. (In Athens, this was usually less than 15 percent of the population and was usually adult males.) All the citizens come together in one place, debate the issues at hand, and then vote. Anything over 50 percent supposedly settled the matter.

Turn Drive Time Into Fun-Filled, History Time With Your Kids! [2]

Our Founding Fathers, however, understood political democracy and opposed it fiercely. For example, James Madison wrote that democracies “have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths” (Federalist #10).

In the Constitutional Convention, Alexander Hamilton said, “The voice of the people has been said to be the voice of God; and however generally this maxim has been quoted and believed, it is not true in fact. The people are turbulent and changing; they seldom judge or determine right.” In a letter to John Taylor in 1814, John Adams wrote, “Remember democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet, that did not commit suicide.”

And then there’s Edmund Randolph, in describing his vision for a senate, said that this house of Congress ought “to provide a cure for the evils under which the U. S. labored; that in tracing these evils to their origin every man had found it in the turbulence and follies of democracy. . . .”

Finally, Fisher Ames, Federalism’s most eloquent spokesmen, wrote: “Liberty has never yet lasted long in a democracy; nor has it ever ended in anything better than despotism.” Without question, the Founders believed that to hand “the majority” political sovereignty was to invite legalized theft, chaos and ultimately tyranny.

Safe for Democracy?

And yet today, most Americans think this nation is a democracy. What happened? When did this shift come, and why?

It’s much easier to narrow down the when than to prove the why. The when lies mostly in the first two decades of the 20th Century. Though the words democracy and democratic had certainly been tossed about before and after the Civil War … no one with any political authority ever labeled the new republic … a democracy. Nope.

Heirloom Audio: Putting God Back Into History! [2]

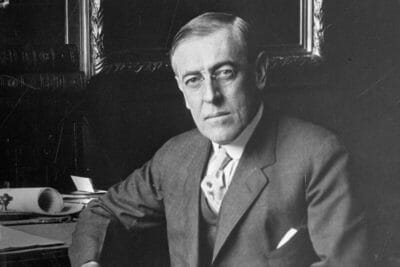

[3]The first blatant attempt to slap that label on the United States came from President Woodrow Wilson in his call for a declaration of war against Imperial Germany (April 2, 1917). In arguing his case before the Senate, Wilson gave us the immortal words, “The world must be made safe for democracy.” And as he moved toward the conclusion of his speech, he said further, “And we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts … for democracy … and for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments.” Wilson seems to give “democracy” an even warmer meaning than the Greeks did, but he also rewrote American history and tradition in the process.

[3]The first blatant attempt to slap that label on the United States came from President Woodrow Wilson in his call for a declaration of war against Imperial Germany (April 2, 1917). In arguing his case before the Senate, Wilson gave us the immortal words, “The world must be made safe for democracy.” And as he moved toward the conclusion of his speech, he said further, “And we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts … for democracy … and for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments.” Wilson seems to give “democracy” an even warmer meaning than the Greeks did, but he also rewrote American history and tradition in the process.

But there’s more. In the middle of his speech, Wilson makes reference to Russia, a faithful ally of Great Britain and France in prosecuting the War:

Does not every American feel that assurance has been added to our hope for the future peace of the world by the wonderful and heartening things that have been happening within the last few weeks in Russia?

What was happening was a murderous revolution that had led to the abdication of the czar. The Provisional Government (that’s what it was called) was clearly less imperial, but it was heavily influenced by Marxist factions. Wilson goes on:

Russia was known by those who knew it best to have been always in fact democratic at heart, in all the vital habits of her thought, in all the intimate relationships of her people that spoke their natural instinct, their habitual attitude toward life. The autocracy that crowned the summit of her political structure, long as it had stood and terrible as was the reality of its power, was not in fact Russian in origin, character, or purpose; and now it has been shaken off and the great, generous Russian people have been added in all their naive majesty and might to the forces that are fighting for freedom in the world, for justice, and for peace.

Seriously? In this speech, Wilson completely reinvents the psyche, character, and history of the Russian people. He also lied about what was happening in Russia in 1917. And he had every reason to know the truth. A few days before his call for war, Wilson had authorized an American passport for the Marxist revolutionary Leon Trotsky. It’s true: Wilson signed off on Trotsky’s plan to return to Russia and turn the Provisional Government into a Marxist dictatorship. So much for democracy. So much for Wilson.

The War Department on Democracy

Another snapshot of an attempt to shape America into a democracy comes from documents published by the War Department. In 1928, the War Department’s U. S. Army Training Manual defined democracy like this:

A government of the masses. Authority derived through mass meeting or any other form of “direct expression.” Results in mobocracy. Attitude toward property is communistic — negating property rights. Attitude of the law is that the will of the majority shall regulate, whether it be based upon deliberation or governed by passion, prejudice, and impulse, without restraint or regard to consequences. Results in demagogism, license, agitation, discontent, anarchy.

But within a few years, there was a call in the Senate to change the manual completely. In fact, by 1952 the U.S. Army was pushing new definitions and a new philosophy of government. Field Manual 21-13, “The Soldier’s Guide,” says:

Meaning of democracy. Because the United States is a democracy, the majority of the people decide how our government will be organized and run – and that includes the Army, Navy, and Air Force. The people do this by electing representatives, and these men and women then carry out the wishes of the people.

Conclusion

The move to the Left was rapid, less than 25 years, at least on paper. And it was accomplished with intention and malice aforethought. Next time we’ll consider why.

For Further Reading:

Gary DeMar, God and Government, A Biblical and Historical Study, Vol. 1 (Atlanta, GA: American Vision, Inc., 1997).

John F. McManus, “A Republic, if You Can Keep It [4],” The New American, 6 Nov 2000.