Paul on Mars’ Hill

Paul on Mars’ Hill

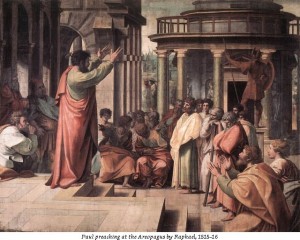

The New Testament records only one sermon of any length directed at a Gentile audience, an audience that knows nothing of the word of God. That sermon is the Apostle Paul’s apologia before the Areopagus in Athens, his sermon on Mar’s Hill. It is recorded for us by the physician Luke in Acts 17.

When Paul first came to Athens, he found the city “wholly given to idolatry.” Someone in Nero’s court had said that it was easier to find a god than a man in Athens. There were many hundreds of them. Paul, moved in his spirit by what he saw as gross sin, immediately confronted those who should have been its chief opponents, the resident Jews and the God-fearing Gentiles. He carried on his disputations in the synagogue and the market place. Some philosophers, both Epicurean and Stoic, came upon these discussions and were puzzled by what they overheard.

Paul spoke of “Jesus” and “Anastasia” (the Greek word for resurrection); the philosophers thought that these might be new gods. They brought Paul before the Areopagus, a court that originally met on Mars’ Hill. Apparently this was a polite inquiry, since Luke, always a careful historian, says nothing of formal charges or any kind of verdict. Luke does say that, aside from the actual officials, the men and women present were the curious and inquisitive, the seekers after the new and marvelous.

Paul’s Approach to Apologetics

As we come to Paul’s defense, it’s also important to think about what he does not say. Paul does not begin with Zeus or Chronus or Uranus. He does not begin from his studies in comparative religion. He does not start with the Good of Plato or the Unmoved Mover of Aristotle. He also makes no appeal to the factual evidence for Jesus’ resurrection. He does not start with redemption at all. He begins with creation. He begins with the God who made the world.

Some have said that Paul does not use Scripture in reasoning with his pagan audience. This is patently false. Though he does not use the customary, “It is written,” nearly every clause or phrase in vv. 24-27 is a paraphrase or summary of some Old Testament passage. (See, for example, Gen. 1:1; Isa. 42:5; 1 Kings 8:27; Isa. 66:1-2; Ps. 50:9-12; and Deut. 32:8.)

Others have said that Paul made a misstep in jumping to the Resurrection without sufficient argument or proof. This is also false. Paul is not trying to prove the Resurrection! He is using the Resurrection to prove the nature of the Last Judgment. He presupposes the historical reality of the Resurrection and of God’s interpretation of it. The philosophers want to know the meaning of the Resurrection. So Paul tells them and it’s not well received.

Finally, many have thought that Paul “cheated” with his appeal to the Unknown God. Not so. The origin of that “strange altar” comes to us through secular writers, and Paul seems to have known this, as he knew quite a bit about the chief character in its story.

The Story of the Unknown God

During the 46 Olympiad (the mid 6th Century BC), a horrible plague desolated Athens. Despite its abundance of gods, Athens couldn’t find one who would or could help. The oracle at Delphi, without further comment, directed them to one Epimenides of Crete, and the Athenians sought him out. Epimenides came to Athens and surveyed the situation. Then he wisely proposed that the Athenians appeal to a God they did not know, but One who could and would help. They decided to ask this God to choose His own sacrifices from flocks of black and white sheep they would let loose. The sheep that laid down on their own would belong to this Unknown God. The Athenians okayed the deal and we’re told the plague ended. The Athenians labeled the altars with the dedication: “To the Unknown God.” In time the altars crumbled and most were destroyed, but the Athenians chose to maintain one as a tribute to the God who had once saved their city.

There’s more. Paul had read the works of Epimenides: he quotes his words in v. 28. And he quotes from the same poem in Titus 1:12. He even calls Epimenides a prophet. Here is the relevant verse from Epimenides:

They fashioned a tomb for thee, O holy and high one—

The Cretans, always liars, evil beasts, idle bellies!

But thou art not dead: thou livest and abidest forever,

For in thee we live and move and have our being.

The point is that it seems perhaps the Creator God, in His infinite compassion visited Athens with mercy once before. The Athenians had misunderstood, twisted, and even suppressed the meaning and significance of that event, but they still had enough of a memory of it to keep the altar at state expense. So Paul is clearly not introducing a brand new god, but simply reminding them of the only true God.

Interpreting the Facts

The facts never speak for themselves. Facts are always interpreted facts. Some Christian apologists don’t understand this. They believe that the empirical evidences surrounding the resurrection of Christ speak clearly to all men, not only of the historical reality of the Resurrection, but also of its theological explanation: The Creator God raised Jesus from the dead. So prove the Resurrection empirically, they say, and you prove the reality of God and the truth of His gospel. The problem with this is that it doesn’t recognize the radical nature of sin, especially in its psychological and noetic effects. The natural man rejects God, not because he lacks evidence, but because he is at enmity with God. He “holds [suppresses] the truth in unrighteousness,” and so his reasoning always leads him to foolishness, idolatry, and wickedness (Rom. 1:18-32).

To the unbelieving Athenians, the whole episode with the Unknown God was only evidence of what all Greeks already believed: The Universe is not only “One” but rational. But at the same time, reality has an “edge” or dimension that is irrational and unknowable. Kant called this the “noumenal” and Barth, “the wholly other.” From this perspective, the Unknown God of the Greeks must be more than unknown, he must also be unknowable. He must transcend or elude all rational categories of thought and phenomenal description.

In this context then, the Resurrection Paul was describing was possible, but only as an irrational manifestation of the unknown and unknowable. Aristotle had a thing for “monstrosities” and maybe this resurrection thing was another interesting freak show. But no matter what, it certainly couldn’t be what Paul was claiming it was.

Paul in his apology rejects the whole Greek system of thought. He challenges the basic presuppositions of his audience. Against the Stoics, he asserts a personal Creator. Against the Epicureans, Paul asserts an immanent and actively involved Lord. Though God is transcendent, He is also the Ruler of the cosmos: He acts in history—and in every moment of history. Paul preaches the Creator’s freedom, His universal providence, and His present demand for repentance from all men. He spanks his audience for their practice and tolerance of idolatry and shows that, even in terms of their own world-view, they are culpable and guilty. It is to this end that he quotes the Stoic poet.

This, then, is the context for the resurrection of Jesus Christ, both as historical fact and theological doctrine. Jesus rose from the dead—He came back to life—in space and time. He did so by His own divine power. His resurrection manifests His eternal deity and His true humanity. And, the resurrection of Jesus points to the resurrection of all men. Death is temporary. The resurrection of Jesus points to God’s final intervention at the end of history: Jesus will judge the world in terms of the Creator’s absolute ethical standard: “his righteousness” (Acts 17:31). There is no escape from history or from judgment. It was time for Athens to repent of her idolatry and her vain philosophical speculations and seek mercy from her Judge. It was time for the Athenians to believe in Jesus Christ.

This, then, is the context for the resurrection of Jesus Christ, both as historical fact and theological doctrine. Jesus rose from the dead—He came back to life—in space and time. He did so by His own divine power. His resurrection manifests His eternal deity and His true humanity. And, the resurrection of Jesus points to the resurrection of all men. Death is temporary. The resurrection of Jesus points to God’s final intervention at the end of history: Jesus will judge the world in terms of the Creator’s absolute ethical standard: “his righteousness” (Acts 17:31). There is no escape from history or from judgment. It was time for Athens to repent of her idolatry and her vain philosophical speculations and seek mercy from her Judge. It was time for the Athenians to believe in Jesus Christ.

Conclusion

Paul’s preaching drew mixed results. Some scoffed, others were willing to hear more later, and we’re told a few believed. But the truth of the Resurrection isn’t determined by majority vote, then or now. God has overcome sin and death for all time. You can settle up with Him now, or He will settle up with you later. This is the powerful message of Easter.

For Further Reading:

Cornelius Van Til, Paul at Athens (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, 1978).

Greg Bahnsen, Always Ready, Directions for Defending the Faith (Atlanta: American Vision/ Texarkana, AR: Covenant Media Foundation, 1996).