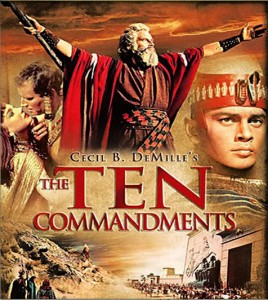

PHARAOH: Every newborn Hebrew man-child shall die. So let it be written. So let it be done.

—The Ten Commandments (Paramount, 1956)

Hollywood isn’t known for its orthodoxy or accuracy when it tries to tell stories from the Bible. Sometimes the problem is the director’s ego: he thinks he can tell a better story than the original Author. (Tolkien, Lewis, and Austen get the same treatment.) Sometimes the problem is unbelief and a real contempt for Scripture. But sometimes the problem is that the scriptwriters simply haven’t read what the Bible actually says.

The story of the baby Moses is good example. Both The Ten Commandments and Prince of Egypt show Moses’ mother setting her son adrift on the Nile in a little homemade ark. We watch as the current carries the basket-like boat along toward an uncertain fate. It’s a moving scene. But it’s not at all what happened.

Moses’ Mother Had a Name

Moses’ mother was named Jochebed (Yocheved in Hebrew). She was a younger daughter of the patriarch Levi and the granddaughter of Jacob and Leah. Her husband was named Amram. He, too, was a Levite—her nephew, in fact, but probably about her age (Ex. 6:20). Amram and Jochebed already had two children when Moses was born, Miriam and Aaron. Their children were a small part of a population explosion that was taking place among the enslaved Hebrew people. That explosion frightened the reigning pharaoh. In fact, it frightened him so much that he thought genocide would be a happy solution:

And Pharaoh charged all his people, saying, every son that is born ye shall cast into the river, and every daughter ye shall save alive. (Ex. 1:22)

The War Against Children

Since the Holocaust, we tend to link genocide with images of the old, the frail, and the emaciated—adults all. But the most practical steps toward genocide usually target the little ones. After all, the elderly probably won’t reproduce and intermarry with one’s hypothetically purer race and corrupt its bloodline. The future lies with the children.

Even in the absence of racism, tyrants are often afraid of a burgeoning population. Tyranny is a difficult art under the best of circumstances, and it far more difficult to control two million than two hundred thousand. But when the population in question is reckoned as subhuman, parasitical, or backward, the fears and difficulties only multiply. Population control becomes a political imperative, zero growth becomes the new gospel, and birth control and abortion become the new sacraments. (Today 78% of Planned Parenthood’s clinics are in urban, minority communities. Planned Parenthood’s founder was a racist to the core.)

But there is another important dimension here. Pharaoh ordered the Hebrew children to be thrown into the Nile. The edict was very specific. Pharaoh’s genocidal holocaust was an offering to the river god, to Osiris, who brought “resurrection” through spring floods to the Egyptian soil each year. Pharaoh hoped for life from death. His genocide was a magical solution to a political problem. It killed two birds with one stone… or with a thousand babies. We should remember this link between ritual magic and racist genocide as it is a dangerous and recurring theme in history.

Motherhood as Political Subversion

When Moses was born, his parents saw something unusual, something beautiful, in the baby. “Goodly” and “fair to God” the Scriptures call the child (Ex. 2:2; Acts 7:20). Amram and Jochebed were evidently convinced that God had marked their son for a great destiny. They could probably guess what that destiny was. God had told Abraham that his seed would descend into Egypt, but come out again in their fourth generation (Gen. 15:16). Jacob, to Levi, to Jochebed, to the baby (four generations). The Hebrew people knew that Egypt was not their real home, as God had promised them the land of Canaan. The time for an exodus was near, and someone would have to lead it. There’s a good chance that Amram and Jochebed believed that their son, if he survived, would become that deliverer.

Amram and Jochebed were also not afraid of Pharaoh’s edict (Heb. 11:23), but they weren’t stupid. They concealed the baby for three months after his birth. Perhaps Jochebed feigned pregnancy during that time to fool her neighbors. It was hard to know who could be trusted (Ex. 2:14). But her neighbors could count to nine, and babies cry at the most inopportune times. So Jochebed attempted a pretty daring strategy.

Jochebed knew where Pharaoh’s daughter usually bathed. Jochebed constructed a little boat out of papyrus and waterproofed it. The papyrus is crucial here as crocodiles don’t like papyrus. Jochebed put her infant son into the boat and set in among the reeds along the river’s brink where the princess was sure to find it. Those reeds probably included papyrus as well. Pharaoh would not let his family bathe in crocodile-infested waters after all. So Jochebed stationed Miriam nearby to see what would happen and to intervene if she could. Then she waited.

Sargon and Moses

Liberal critics have accused Scripture of plagiarizing this story. They say that an earlier tale describes another baby abandoned in a river. The baby in that story grew up to be Sargon of Akkad, the first empire builder:

My mother, a high priestess, conceived me, in secret she bore me. She placed me in a reed basket, with bitumen she caulked my hatch. She abandoned me to the river from which I could not escape. The river carried me along: to Aqqi, the water drawer, it brought me. Aqqi, the water drawer, when immersing his bucket lifted me up. Aqqi, the water drawer, raised me as his adopted son. (Brian Lewis, The Sargon Legend, 1978)

The date of this Sargon legend is in question; it may come from the 7th century BC during the reign of Sargon II. But assuming for the moment that the legend did predate Moses’ birth, what then? The Hebrew people weren’t stupid. Doubtless, Jochebed had heard of Sargon the Great. If this story of Sargon’s abandonment and rescue was in circulation, Jochebed could easily have seen the possibilities. Pharaoh’s daughter was apparently barren; she could give her father no heir to the throne. Then suddenly the Nile, the divine source of resurrection and rebirth, hands her a child, the same way another river gave the world its first emperor. Surely Pharaoh’s daughter would see destiny writ large in the whole affair. The child’s immediate safety and future destiny would be ensured. But legend or no, Jochebed’s plan was brilliant.

Of course, no amount of strategy and plotting could guarantee the outcome. The baby was clearly Hebrew. His circumcision, if nothing else, would give that away. The princess might reject the baby as subhuman and she might even throw him into the Nile as her father’s edict required. Her heart and the baby were in God’s hands, and Jochebed understood this.

Pharaoh’s daughter claimed the baby as her own. She named him Moses, “drawn out,” since she had drawn him out of the water. At this point Miriam stepped in and suggested a Hebrew nurse for the child. The princess agreed and hired Jochebed to nurse the royal foundling. God has a sense of humor.

The Education of a Prince

In Hebrew culture it took about three years to wean an infant. It seems the Egyptians took a little longer. Egyptian mothers routinely surrendered up their children to tutors or teachers around age four—that is, if those children were going to receive any sort of formal education. Most children were taught by their parents and never learned to read and write at all. But Moses was “learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians.” (Acts 7:22)

Princes like Moses attended palace schools where they were taught by scribes and priests. Writing was the chief area of instruction. Under this discipline, Moses would memorize Egyptian literature and samples of literary forms. He would need to know the traditional and historic Egyptian precedents. Along the way, he would learn something of arithmetic and geometry (a prince after all, might oversee the construction of public works), the equipping of an army, or the taxation of the nation. Moses would study geography and perhaps learn a foreign language or two. He might serve as a diplomat, an overseer of foreign commerce, or a governor of some newly acquired province. Moses would learn some astronomy and a great deal about the calendar – these were things that were crucial to Egyptian agriculture and religion, and a prominent prince would certainly have his hand in them. Moses would study medicine and the thousand amulets and charms connected with that discipline – educated people knew about such things, and a prince could not appear ignorant. Moses would read the wisdom literature that promoted a pragmatic humanitarianism – all the princes did. And, of course, Moses would learn the mythology of Egypt, for it explained the origin and nature of Egyptian culture, and the role of Pharaoh within that culture.

The education of an Egyptian prince was functionally utilitarian, ethically pragmatic, and inescapably magical. Religious polytheism and a magical understanding of reality were the givens, the presuppositions, of Egyptian educational theory and practice. This is the gauntlet that Moses would have to run one day, and Jochebed knew and risked this.

Training Resistance Leaders

Jochebed had four years to prepare her infant son for spiritual combat, four years to ground him in Hebrew theism and theistic ethics. She had four years to teach him to walk with God. She succeeded. But neither her success nor her methods are unique. Christian education and nurture are not mysterious (or magical in any way). Neither is it abstract or difficult to understand. It is a matter of living faith, spiritual discipline, and hard work.

First of all, godly parents ought to teach their children the forms and basic summaries of the Christian faith: the Apostles’ Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Ten Commandments, for example. Parents should teach their children the stories (histories) of the Bible in order and from the text of Scripture itself. They should help their children memorize passages of Scripture, both those that summarize the gospel and those that address the child’s immediate needs and duties: trusting God, obeying parents, working cheerfully, being thankful, etc. All of these things should involve many explanations and a lot of questions and answers. A simple catechism (a series of set questions and answers) may help. It’s also important that parents teach their children to sing the songs of the faith, particularly those that are rich in theology or that celebrate God’s great acts in redemptive history. (Being sort of non-musical, I wasn’t very good at this one.) And parents should teach their children to pray earnestly.

These are the forms. In themselves they are insufficient; they can even become sterile and mechanical. Godly parents must live out the reality of these things with and before their children. Children have to see their parents studying Scripture, trusting God in hard times, singing His praises joyfully as a matter of course, and seeking Him diligently in prayer. Children must discover the joy and love of God in their own parents. Parents and children must walk with God together day by day and hour by hour.

Conclusion

Moses delivered Israel from Egypt, wrote the Torah, and prepared the world for Christ. His mother prepared him for that work, and all his higher education in foreign magic couldn’t undermine the foundations she laid. Post-modern America is a lot like Egypt. The world today will tempt your children with shortcuts, ritual magic and ungodly solutions to the problems they will face. We need godly parents like Amram and Jochebed. Are you raising your children in terms of Egyptian-American “power from below”? Or will your children be firmly planted in God’s holy word like Moses?

We rebuild America with our children. Children are the key. That’s why pharaohs kill them. That’s why the left hates them. Don’t think for a second that angry union teachers care about your kids. They don’t.

For further reading:

George Grant, Killer Angel: A Short Biography of Planned Parenthood’s Founder, Margaret Sanger (Frankline, TN: Ars Vitai Press, 2001).

John Piper, Desiring God, “When Is Abortion Racism?” https://www.desiringgod.org/resource-library/sermons/when-is-abortion-racism

James Patrick Holding,“Was the story of Moses stolen from that of the Assyrian king Sargon?” https://www.tektonics.org/copycat/sargon.html

Tedd Tripp, Shepherding a Child’s Heart (Wapwallopen, PA: Shepherd Press, 1995).

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living