In its basic elements, the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 served as the primary model for the United States Constitution. Those essential elements included a constitutional convention, popular ratification, the bill of rights, separation of powers, and an independent judiciary.

In its basic elements, the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 served as the primary model for the United States Constitution. Those essential elements included a constitutional convention, popular ratification, the bill of rights, separation of powers, and an independent judiciary.

Drafted by John Adams, the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 notably had a well-developed doctrine of separation of powers. It provided for a genuine system of checks-and-balances: a two-house legislature, a strong executive with veto power, and an independent judiciary with life tenure.

One article of this model for our national Constitution stated, “It is the right of every citizen, to be tried by judges as free, impartial and independent as the lot of humanity will admit.” And it first contained guarantees of “a government of laws and not of men.”

A Timeline of the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780

Stable Government Since 1691

In 1691, the Charter of Massachusetts Bay established the Royal Government, with a considerable degree of liberty and self-government that lasted until the Revolution. The 1691 Charter left the strong local government that had evolved during the seventeenth century unchanged.

Boston Tea Party

December 16, 1773

The Sons of Liberty protested “no taxation without representation” and dumped tea into Boston Harbor, which incited tea parties in other colonies.

Parliament Retaliates

May and June 1774

The five Coercive Acts, sometimes called the Intolerable Acts, closed Boston Harbor to all commerce, provided for British officials accused of crimes to be tried in England or Nova Scotia, summarily replaced the Council with Royal appointments to serve at the King’s pleasure, and allowed the Governor to quarter troops in Boston. General Thomas Gage was also made Governor and given greater powers to appoint and remove judges, sheriffs (which appointed juries), and other local officials without the consent of the Council. These acts changed the basic structure of government that had existed since the 1691 Charter.

General Court Dissolved

June 1774

General Gage dissolved the General Court when the people of Massachusetts rebelled against the changes to government and the British occupation.

Three Provincial Congresses

October 1774 to June 1775

Ninety representatives nevertheless met in Salem and organized themselves into a Provincial Congress because General Gage’s action was “unconstitutional, unjust and disrespectful.” Three Provincial Congresses, wholly without legal status, governed Massachusetts until June 1775.

Lexington & Concord

April 19, 1775

Things got worse. The Provincial Congress deposed General Gage as Governor because he ordered British troops to secure the gun powder in Concord and seize Samuel Adams and John Hancock, rumored to be in Lexington.

John Adams Argues Before the Continental Congress

May 1775

Without a Governor and with the General Court dissolved, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress turned to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia and requested “explicit advice” about “the taking up and exercising the powers of government.”

“I embraced with joy the opportunity of haranguing on the subject at large,” wrote John Adams, “and urging Congress to resolve on a general recommendation to all the States to call conventions and institute regular governments.”

Berkshire Constitutionalists Drop the Pretense

December 1775

Insistent that the 1691 Charter was dissolved by war, the Berkshire Constitutionalists defied its continuing validity by closing the courts in disobedience. Pittsfield protested that if the pretense is “adopted by the people we shall perhaps never be able to rid ourselves again” of British rule. Since the suspension of government, they had been in a State of Nature and “lived in peace, Love, safety, Liberty and Happiness.” Strockbridge declared: “When we deviate from the established rules, we are lost in the boundless field of uncertainty.”

All Provinces to Establish New Governments

May 1776

From Philadelphia, the Continental Congress advised all the provinces to establish new governments. The Massachusetts General Court ordered that courts be run under the name of the “Government and People of Massachusetts Bay.”

Independence Day

July 4, 1776

On a bright morning in Philadelphia, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence.

Difficult and Dangerous Business

1776 to 1780

It would take the next four years for Massachusetts to adapt the consent of the governed from a political theory to a political process. To John Adams this was “most difficult and dangerous business,” with more peril in the experiment in self-government “than from all the fleets and armies of Great Britain.”

Who Drafts a Constitution?

September 1776

The House of Representatives petitioned the towns requesting permission to “enact” a constitution in consultation with the Council.

Concord Calls for a “Convention”

October 22, 1776

Concord objected, arguing that the General Court was not competent, because a constitution should secure the people in their rights against the government. A constitution that is both enacted and “alterable by the Supreme Legislative is no Security at all.” Concord was the first to call for a special “Convention,” not part of the General Court, for the sole task of framing a constitution. Other towns expressed similar sentiments. Attleborough asserted that “the End of Government is the Happiness of the People; so the Sole Power & right of forming a Plan thereof is essentially in the People.”

Numerous towns demanded ratification by the people, whether the constitution was drafted by the legislature or by the convention.

Legislature Frames the Constitution of 1778

The House of Representatives ignored the dissident towns and, with the Council, drafted the Constitution of 1778. It did, however, submit it to the people as a whole, with adoption to take effect with two-thirds approval.

Constitution of 1778 Rejected

The towns decisively rejected the General Court’s constitution by a six-to-one margin. Theophilus Parsons, who drafted the influential Essex Result, agreed with the farmers in Pittsfield that a State of Nature was surely preferable. Not only was there not a constitutional convention, but the failed draft of 1778 did not have a bill of rights, it condoned slavery, did not ensure the separation of powers, etc.

Constitutionalists Demand Action

August 26, 1778

The Berkshire Constitutionalists continued to agitate for a true constitutional convention and kept their courts closed “rather than to have Law dealt out…without any Foundation to support it, for…we should before this time have had a Bill of rights, and a Constitution.” On August 26, the eighteen towns that met in Pittsfield threatened to join with another state if a special constitutional convention were not called.

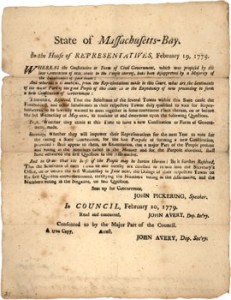

General Court Asks the People

February to June 1779

The General Court petitioned the towns in February of 1779 whether they first “chuse, at this time, to have a new Constitution or Form of Government made” and second whether they should authorize “a State Convention, for the sole purpose of forming a new Constitution.” In June, the General Court issued a call for the election of special delegates for a convention because “a large majority of the inhabitants” from more than two-thirds of the towns “think it proper to have a new Constitution.”

Historic Constitutional Convention

September 1, 1779

The Convention gave life to the phrase, “We the People,” and, as such, has been recognized as perhaps “the greatest institution of government which America has produced, the institution which answered, in itself, the problem of how men could make government of their own free will.”

John Adams Drafts the Document

September 1779 to March 1780

On September 4, 1779, the Constitutional Convention elected a committee with members from each county to prepare a draft Declaration of Rights and a Frame of Government. The task was delegated to a three-member subcommittee of James Bowdoin, Samuel Adams, and John Adams, the last of whom was selected to draft the document. He finished his work in October. The draft constitution was submitted to the full Convention on October 28, 1779, which debated it until November 12, with John Adams present, and then again from January 27 to March 1, 1780, without him. The Convention made several important changes to Adams’s draft.

Ratification

March to June 1780

Copies of the Constitution and an Address, a rationale to improve its chances because of the repudiation in 1778, were submitted to the towns for ratification by a two-thirds majority. Even with optimism about the War for Independence at a low point, at least 188 towns responded.

The Convention reconvened on June 7 to consider the response of the towns and ultimately ratified the Constitution on June 15. The next day, a proclamation by James Bowdoin, President of the Constitutional Convention, announced that the Constitution would go into effect on the last Wednesday of October 1780 at the first meeting of the General Court.

Samuel Adams Writes to John Adams

On July 10, 1780, Samuel Adams wrote to John Adams, that most passionate and influential advocate for constitutional government: “This great Business was carried through with good Humour among the People.”

Constitutional Government Begins

Following an election, at the first meeting of the General Court on October 25, 1780, John Hancock took his constitutional oath of office as the first Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The Supreme Judicial Court held its first official sitting on February 20, 1781.

Auspicious Omens

On November 12, 1780, the Massachusetts Line, comprised of the military officers still fighting the War of Independence, addressed the General Court. Considering themselves “as citizens in arms for the defense of the most invaluable rights of human nature,” the officers were at “a loss to find the terms sufficiently expressive of our veneration and gratitude for the illustrious Convention” and “highly respect and approve” of the resulting Constitution. Still at war, but with “grateful hearts,” they nevertheless felt the “most auspicious omens” for the future.

The Last Word

The last word of this timeline goes to John Adams who marveled that he had “been sent into life at a time when the greatest lawgivers of antiquity would have wished to live. How few of the human race have ever enjoyed an opportunity of making an election of government, more than air, soil, or climate, for themselves and their children!”

©2012 Off the Grid News

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living