On March 23, 1775, delegates from every county in Virginia met at St. John’s Church in Richmond to discuss the situation with the British. They were also there to elect the delegates to the coming Second Continental Congress. They did not meet in Williamsburg, Virginia’s capital, because they feared that the British Governor of the colony might arrest them and ship them all back to England to face trials as traitors.

On March 23, 1775, delegates from every county in Virginia met at St. John’s Church in Richmond to discuss the situation with the British. They were also there to elect the delegates to the coming Second Continental Congress. They did not meet in Williamsburg, Virginia’s capital, because they feared that the British Governor of the colony might arrest them and ship them all back to England to face trials as traitors.

Instead, the Virginia delegates met fifty miles inland, where they hope to be protected. Everyone knew that the British would send reinforcements to Boston in the aftermath of the uprisings, and more fighting would take place. Plus they were also well aware that there were colonists opposed to breaking from Great Britain. These were not safe times.

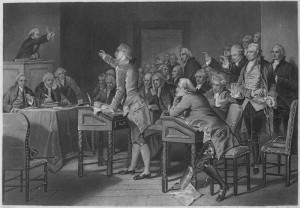

Patrick Henry, age thirty-eight, did not agree with those who were content with personal safety. He was certain the British would eventually overwhelm Massachusetts patriots unless the other colonies came to their aid. In what became one of the most famous speeches in the history of America, Henry presented resolutions for equipping the Virginia militia to go to the aid of Massachusetts. Both thirty-one-years-old Thomas Jefferson and forty-three-years-old George Washington were thrilled by the fiery speech. It ended with the following plea for immediate action:

Gentlemen may cry peace, peace. But there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?

Henry’s attitude was that of a condemned galley slave. His back was bent as though under the weight of approaching death. After a solemn pause, he raised his eyes toward Heaven. Before his entranced audience he held up his crossed wrists, bound by imaginary though palpable chains. Then, he slowly prayed in words rising to a fever pitch. Henry bent his body backward, his chained hands raised over his head.

Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take …

He clenched his right fist as though holding a knife pointed at his heart. As he drove the imaginary dagger into his chest, he proclaimed:

… but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

They pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor so that we could be free!

As young Patrick Henry shouted the word “liberty,” his imaginary chains were broken and his arms set free. He stood erect and defiant, his face aglow. And then he waited as the word “liberty” echoed throughout the church.

As one witness later reported, “His attitude made him appear a magnificent incarnation of Freedom.” Another listener was so overcome by Henry’s powerful speech that he exclaimed, “Let me be buried on this spot.”

The resolutions passed, and Henry was appointed commander of the Virginia forces. The next year, 1776, he became the first elected governor of Virginia.

In many ways Patrick Henry’s personality made him a counterbalance to the refined logic of Jefferson, the well-tempered industry of Franklin, and the unyielding honor of Washington. By many accounts, he had been an idler throughout his younger life (and some would say a derelict). Though all in his family recognized his brilliance, by the time he had reached the age of ten they knew he would never be a farmer. At age twenty-one his father set him up in a business that he bankrupted shortly thereafter. Finally, the general public disgust in Hanover and pressure from his young family (he had married at the age of eighteen) caused him to study for six weeks and take the bar exam, which he passed, and begin work as a lawyer.

After rising to recognition as a lawyer, Henry began to earn the reputation as a firebrand for liberty. He wasn’t just a speech maker, however. At the outbreak of the revolution, he returned to his native state and lead militia in defense of Virginia’s gunpowder store, when the royal Governor spirited it aboard a British ship. Henry forced the Governor Lord Dunmore to pay for the powder at fair price.

After 1776, Henry was re-elected for three terms as governor of Virginia, succeeded by Thomas Jefferson, and then elected again to the office in 1784. Patrick Henry was a strong critic of the constitution proposed in 1787. He was in favor of the strongest possible government for the individual states and a weak federal government.

©2012 Off the Grid News

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living