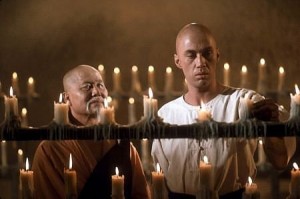

Caine: What is the best way to deal with force, teacher?

Teacher: As we prize peace and quiet above victory, there is a simple and preferred method—run away.

—Kung Fu, Warner Brothers (1972)

One should not employ force if he may save himself by flight….

—Francis Schaeffer, A Christian Manifesto (1981)

“Run Away”

For three seasons in the mid-70s, Kwai Chang Caine wandered the American West, righting wrongs and defending helpless underdogs. Caine was a Shaolin priest and a master of the martial arts. The series was called Kung Fu (ABC).

We learned through flashbacks that Caine had fled China after killing the nephew of the reigning emperor. Bounty hunters and imperial assassins dogged his trail, and local evils presented new threats and challenges every week. And so, though Caine disdained violence and direct confrontation, circumstances regularly compelled him to use the arts of war.

Kung Fu brought together the counter-culture’s fascination with Eastern philosophy and America’s love affair with the vigilante justice of the American Western. In every episode the man of peace had to use (what were then) mysterious skills to defend the innocent and bring down the violent. And he did it all without firing a shot.

Kung Fu brought together the counter-culture’s fascination with Eastern philosophy and America’s love affair with the vigilante justice of the American Western. In every episode the man of peace had to use (what were then) mysterious skills to defend the innocent and bring down the violent. And he did it all without firing a shot.

But the series was philosophically dishonest. It left us to read Caine’s flight from the emperor and his protection of the innocent in Christian terms. We were told the Shaolin monks “prize peace and quiet above victory.” But the Shaolin (or Buddhist) understanding of peace rests on “monistic” premises: all things are one thing. (Your checkbook isn’t really yours… it belongs to the group… the one.) Tranquility is the recognition of that essential unity. The Buddhist concern is not with justice or social order, or even love for one’s neighbor. For Buddhism, “compassion” (karuna) is unselfishness, dying to the illusion of individuality. “For the Buddhist the practice of unselfishness is simply part of the overall technique of divesting oneself of the illusion of self” (Guinness, 224).

Caine’s flight from the Chinese authorities—his civil disobedience—and his regular use of muted violence should have been presented in these terms on the show. They weren’t, and Caine came across as an Asiatic Lone Ranger—minus the silver bullets and white horse.

David on the Run

The book of First Samuel shows us another hero on the run. His name is David. Like Caine, he was running away from his king. Like Caine, he avoided bloody confrontation though he was a skilled warrior. That’s about as far as the similarities go.

David’s story begins with Saul’s apostasy. Saul turned from God and Yahweh sent an evil spirit to torment him (1 Sam. 16). Saul’s advisors suggested music to sooth his soul. Someone came up with the name of a skilled harpist: David, the son of Jesse, a shepherd boy from Bethlehem. So Saul’s advisors sent for the boy, and he became the court musician and one of Saul’s many armor bearers. What no one at court knew was that the prophet Samuel had already anointed David to be the next king of Israel.

When the Philistines stepped up their aggression and their champion, the giant Goliath, bellowed out defiance against Yahweh and Israel, Saul sat in his tent, paralyzed—even though Saul was head and shoulders taller than everyone in Israel. But David, acting in faith, took up what should have been Saul’s role: with a sling and a stone, he became Israel’s champion (2 Sam. 17). David’s victory turned the tide of battle and sent the Philistines running.

Saul’s son, Jonathan, immediately grasped what had happened. With great humility and faith, he relinquished his robe and weapons to David and so recognized him as Israel’s next king. Saul was a little slower on the uptake. But when the women of Israel greeted the new captain David with songs of praise, Saul finally understood. “And Saul eyed David from that day and forward” (2 Sam. 18:9).

Twice, when demonic madness was upon him, Saul tried to pin David to the wall with a javelin (v. 11). Each time David escaped. Then Saul sent him into battle, hoping the Philistines would kill him. When all of this failed, Saul ordered David’s death. Jonathan intervened, but Saul’s envy soon reawakened. He threw his javelin at David a third time. David fled, and for the next several years, he was on the run. First, he went over to the Philistines (ch. 21). Then, he hid in the wilderness (ch. 22). Finally, he returned to the Philistines until the day Saul fell in battle (ch. 27).

During these long years, Saul descended further into madness and murder. He slaughtered the priests of Yahweh and their families (1 Sam. 21). He chased David throughout the wilderness of Judah. In the end he went to a witch to call up the ghost of Samuel. That went badly (1 Sam. 28), and Saul died by suicide in the midst of battle (1 Sam. 31). A short time later, David was crowned king of Judah and, seven years later, king of a united Israel (2 Sam. 2-5).

Passive Civil Disobedience

David is a classic example of biblical civil disobedience. He ran from Saul, deceived him, left his jurisdiction, sought refuge with his enemies, and was willing to take refuge in a city that might support his cause (1 Sam. 19—24). And though he became the captain of a small army, he never went into battle against Saul or the armies of Israel.

We can use one incident from David’s wilderness adventures to highlight his attitude toward King Saul (ch. 24). Saul was chasing after David, but stopped long enough to find a restroom. He found a cave. David and his men were hiding in its sides. David’s men pressed him to eliminate Saul there and then. They saw it as a God-given opportunity and trumped up divine promises to spur David to action. David flatly refused. He did, however, cut off the skirt of Saul’s robe.

We can use one incident from David’s wilderness adventures to highlight his attitude toward King Saul (ch. 24). Saul was chasing after David, but stopped long enough to find a restroom. He found a cave. David and his men were hiding in its sides. David’s men pressed him to eliminate Saul there and then. They saw it as a God-given opportunity and trumped up divine promises to spur David to action. David flatly refused. He did, however, cut off the skirt of Saul’s robe.

The king’s robe was a sign of his office. More than that, the “skirt” (kanaph) or “wing” bore the blue fringe or ribbon that marked every Israelite as a son of the Law and a member of God’s heavenly host (Num. 15:37-41). By removing this fringe, David was symbolically attacking Saul’s office and excising him from God’s host.

When David had time to think about this, he regretted what he had done. He knew he had overstepped his authority. He told his men, “Yahweh forbid that I should do this thing unto my master, Yahweh’s anointed” (1 Sam. 24:6). David followed Saul out of the cave and called after him. He told Saul what he had already told his men: “I will not put forth my hand against my lord; for he is Yahweh’s anointed” (v. 10). Rather than initiating hostilities, David appealed his cause to God: “Yahweh judge between me and thee, and Yahweh avenge me of thee: but my hand shall not be upon thee” (v. 12).

The Theology of Civil Disobedience

We must understand David’s flight from Saul in terms of the biblical doctrine of creation. As Creator, Yahweh is the Source of all legitimate authority and power. But God delegates some of His authority to men. “The powers that be are ordained of God” (Rom. 13:1). God has ordained family, church, and civil government to share in the government of His world. He has given these institutions His word as the only infallible revelation of His will. Those who bear authority in the family, church, and State are obligated to rule in terms of that infallible word: they ought to submit their actions and judgments to the law of God. While each of these covenantal institutions has its own proper sphere and powers, they are still interdependent and coordinate in their operations. They all work for God, whether they understand that or not.

We must understand David’s flight from Saul in terms of the biblical doctrine of creation. As Creator, Yahweh is the Source of all legitimate authority and power. But God delegates some of His authority to men. “The powers that be are ordained of God” (Rom. 13:1). God has ordained family, church, and civil government to share in the government of His world. He has given these institutions His word as the only infallible revelation of His will. Those who bear authority in the family, church, and State are obligated to rule in terms of that infallible word: they ought to submit their actions and judgments to the law of God. While each of these covenantal institutions has its own proper sphere and powers, they are still interdependent and coordinate in their operations. They all work for God, whether they understand that or not.

As long as those who hold authority obey God’s law, we are to submit to their rule (1 Pet. 2:15-17). But when a ruler (magistrate, elder, parent) uses his God-given authority to break God’s law or to harm God’s people, the other rulers at hand ought to oppose him—each with his own proper powers. And so a church might excommunicate a murderous king. A state governor might oppose federal usurpations. The city police might arrest an abusive parent. A godly parent might ask a federal court to defend his family against a lawless federal agency.

But what should we, as individual citizens, do when we face such tyranny? Wherever possible, we ought to appeal to other God-given authorities for help and protection. We should call upon the church elders, call the police, and appeal to the courts. What if all levels and sorts of government are corrupt or simply unable to provide the necessary help? Sometimes we must simply submit to the tyranny and kiss the rod of God’s judgment. This is what God required of Israel during the Restoration Era. But when the tyrant commands us to violate God’s law, then we must respectfully refuse. We must obey God rather than men (Acts 5:29). And if the tyrant tries to kill us, then we must flee and—like David—wait on the justice of God.

Conclusion

David was a bloody man; he was not pacifist (1 Chron. 22:8). He valued the peace of God’s law-order, but he knew that military victory was at times necessary to maintain it. He didn’t run from Saul for the sake of peace as such, but for the sake of God’s law and out of respect for God’s chain of command. In time God heard his prayer and brought judgment on Saul. David was able to ascend the throne with a clear conscience and an unsullied record.

Ours is an age of tyranny, injustice, and lawlessness in high places. The temptation to private violence is a strong one. But God has committed the sword to the civil magistrate and allows it to individuals only for self-defense in extreme circumstances (Rom. 13:4; Ex. 22:2-3). God doesn’t want an army of lone-gunmen, of revolutionaries and terrorists, who live and die by the sword (Matt. 26:52; Rev. 13:10). The power of His kingdom is in the gospel, and that Spiritual sword has the power to overturn tyrants and bring down empires. It has done it before; it will do it again.

For Further Reading:

Os Guinness, “The East, No Exit,” in The Dust of Death, A Critique of the Counter Culture (Downers Grove, InterVarsity Press, 1979).

Peter Leithart, A Son to Me, An Exposition of 1 & 2 Samuel (Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2003).

Francis A. Schaeffer, A Christian Manifesto (Westchester, IL: Crossway Books, 1981).

Samuel Rutherford, Lex, Rex, or The Law and the Prince (Harrisonburg, VA: Sprinkle Publications, 1982 [1644]).

Junius Brutus, A Defense of Liberty Against Tyrants (Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos). (St. Edmonton, Canada: Still Waters Revival Books, 1989 [1689]).

Gary North, Lone Gunners for Jesus, Letters to Paul J. Hill (Tyler, TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1994).

©2012 Off the Grid News

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living