I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body….

—Charles Dickens on the first penitentiary (1842)

I told them [the Texas legislature] that the only answer to the crime problem is to take nonviolent criminals out of our prisons and make them pay back their victims with restitution.

—Chuck Colson, Transforming Our World (1988)

Beneath the Eye of God

Eastern State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania was the first-born child of the prison reform movement in early America. Unlike earlier prisons, the penitentiary was designed, not to punish the inmate, but to move him toward spiritual reflection, conviction, and reformation. The key to this reformation was complete isolation from other prisoners. The inmate would be left alone with a Bible and a bit of manual labor. Thus abandoned to his thoughts and the words of Scripture, the prisoner would surely face his crimes and guilt and respond with revulsion and regret. He would become a true penitent. And so this new sort of prison was called a “penitentiary,” and its rooms were called “cells.” Until that time—the year was 1829—a cell was a room in a monastery.

The first American prison, Eastern State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania, was designed after a monastery.

The theology behind the project was largely that of the Quakers, though it was sprinkled liberally with Enlightenment thinking. The project assumed that every man was open to God’s self-revelation. Meditation, solitude, and spiritual education would (in theory) work inner transformation and bring forth life from death. And, should the method fail, the years of isolation would still be sufficient punishment for past crimes and an effective deterrent against future ones as no one would ever want to come back to the unimaginable loneliness of Eastern State Penitentiary.

The man who gave this first penitentiary form was British-born architect John Haviland. “Haviland’s ambitious mechanical innovations placed each prisoner in his or her own private cell, centrally heated, with running water, a flush toilet, and a skylight.” The skylight was called “the Eye of God.” It was supposed to remind the inmate of God’s immediate presence as judge and deliverer. Haviland used “the grand architectural vocabulary of churches” throughout the interior of the prison. In other words, he designed the interior of the penitentiary to look like a medieval church or monastery.

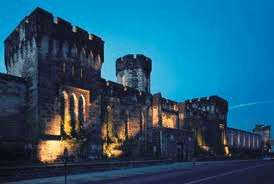

He employed 30-foot, barrel vaulted hallways, tall arched windows, and skylights throughout. He wrote of the Penitentiary as a forced monastery, a machine for reform. But he added an impressive touch: a menacing, medieval façade, built to intimidate, that ironically implied that physical punishment took place behind those grim walls. (https://eassternstate.org)

The façade was done in heavy Gothic. It looked like a castle wall, complete with massive, crenellated towers.

Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont visited Eastern State Penitentiary in 1831. They wrote a laudatory report to the French government, but they didn’t think such an institution would work in France. The French people weren’t religious enough. Charles Dickens, on the other hand, had quite a different reaction. In his American Notes for General Circulation, he wrote:

I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body; and because its ghastly signs and tokens are not so palpable to the eye and sense of touch as scars upon the flesh; because its wounds are not upon the surface, and it extorts few cries that human ears can hear; therefore I the more denounce it, as a secret punishment in which slumbering humanity is not roused up to stay.

Restitution and Restoration

Israel’s civil laws have been called brutal and barbaric. But interestingly, Israel had no prisons or jails. The ancient penal system didn’t use psychological torture to rewrite the character and personality of the convicted criminal. In fact, Israel’s civil laws show only an indirect concern for the reformation or rehabilitation of the lawbreaker. As far as Scripture is concerned, such matters are not the province of the State or of civil society generally. Scripture leaves the cure of souls to the gospel ministry. The Mosaic laws had as their chief concern the welfare the victim, not the criminal. The sanctions prescribed by the Mosaic law emphasized restitution to the victim and the restoration of the society to good and peaceful order.

Theft

The Mosaic law designated multiple restitution as the proper punishment for theft (Ex. 22:1-4). If the thief was caught with the stolen goods, he had to make two-fold restitution. That is, he had to give back what he stole and an equivalent amount in goods or money. If he stole a sheep, he had to restore two. But if the thief had destroyed what he had taken, or put it beyond recovery, then the level of restitution went up—four sheep for a sheep and five oxen for an ox. If the thief could not make the payment, he would be sold into penal service, and the price of that service would go to the victim. But the thief wouldn’t be incarcerated with hundreds of other criminals while he labored. Rather, he would work off his debt in the employ of a private citizen and in the context of that man’s family and local community. He wouldn’t be shut off from his wife and family or from public worship. And when his debt was paid, he was free.

Destruction of Property

Israel’s laws also addressed the accidental or intentional destruction of another’s property (Ex. 21:5-6). For example, a man who turned his animal into somebody else’s field was responsible to restore whatever the animal ate in that field. The restitution was to be from the best of his own crops. Second, a man who started a fire was responsible for the damage the fire caused, even if the damage was accidental. He was to make such restitution as he was able. These laws would have broader applications to other forms of indirect theft such as the pollution of a stream or lake.

Seduction

The concern for restitution also appeared in the laws governing seduction (Ex. 22:16-17). The assumption here was that the man involved was not a repeat offender or a violent psychopath (cf. Deut. 21:18-21); he might simply have been the girl’s boyfriend or fiancé. The legal consequences for the man were twofold.

First, the girl’s father was to decide whether or not the two should be married. If the seducer was generally irresponsible and immoral, the father could send him packing. On the other hand, if the seducer was a generally responsible and honorable man—though one who had fallen into serious sin—the father could insist that he marry the girl. In both cases, the law was concerned with the victim and her future.

Second, the seducer had to pay the girl’s dowry, which could be a considerable sum. The law was fiercely realistic at this point. Obviously no amount of money could make up for what had happened to the girl. But the dowry money would be useful. If the girl married her seducer, she would come into the marriage with a good deal of money—money that would not be property of her new husband. She would have financial independence within the marriage. If the girl didn’t marry, she would be in a good financial position when the right man did come along. Either way, the money would provide insurance and security for her future.

What About the Rich?

Could a greedy rich guy thumb his nose at these laws? Possibly, for a while. After all, a wealthy man could easily afford to part with a few sheep or an ox or two. As long as his thefts were well below the level of his income, a rich man would always be able to make proper restitution. He would never have to worry about the threat of doing jail time for his crimes. To some, this inequality seems to call the justice of the Mosaic law into question. But like it or not, this law was God’s law, and if the rest of the Bible is correct… God doesn’t fail in justice at this point or any other. This is tough stuff for the modern mind as His means and timing are not always ours. But there are a couple things to think about.

First, the law’s primary concern was restitution to the victim, not the suffering of the perpetrator. All sanctions enforced by human government are necessarily imperfect in their scope and depth. Man can’t view the crime or the heart of the criminal with divine omniscience, and he could never match the crime with perfectly equal sanctions. God will do that on Judgment Day. In the meantime, there must be civil sanctions for the maintenance of civil society and the protection of the innocent. God told Israel in no uncertain terms what those penalties ought to be.

Second, inequality of circumstances does not automatically require a graduated penalty for the law-breaker. There is no logical reason a fine should increase simply because someone can easily pay it. (The same is true of speeding tickets today. It’s easier for a millionaire to pay a $100.00 fine than it is for someone making $20,000 a year.) The socialist balks at this because he sees inequality of condition as inherently unjust. Scripture looks upon it as the work of God’s providence. And because God’s providence surrounds all of us in all that we do, no one can blame his inequality of circumstances for his crimes, nor may he require inequality of punishment for someone else’s. Whether we like it or not, God has set inequality in the Earth (Prov. 22:2). Again, tough stuff to swallow for most of us moderns.

Third, the law did allow Israel’s judges to impose corporal punishment when they thought it appropriate (Deut. 25:2-3). A man rich enough to laugh at fivefold restitution probably wouldn’t laugh off the whipping the judges might impose for callousness, arrogance, or flippancy toward the victim or the court. Repeated offenses, especially if they involved violence, might bring an even greater sanction. Lastly, the bad news for rich guys who thought they could buy their way out of trouble is that the Mosaic law required the execution of habitual criminals (cf. Deut. 21:18-21). Ouch!

Conclusion

Restitution is more than an Old Testament concern. The issue appears explicitly in the New Testament. When the tax collector Zacchaeus came to repentance, he said to Jesus, “Behold, Lord, the half of my goods I give to the poor; and if I have taken anything from any man by false accusation, I restore him fourfold” (Luke 19:8). In response, Jesus said, “This day salvation is come to this house” (v. 9). Zacchaeus’s restitution was evidence of the sincerity of his faith as well as soothing to his own conscience. Most certainly it was welcome help to the victims of his legalized plunder.

But the “big picture” theme of restitution in both Testaments is much greater than the individual case laws. The prophets and apostles tell us that the goal of redemption is the “restitution of all things” (Acts 3:21; Matt. 19:28; Isa. 65:17-25). The redemption that Jesus purchased on the Cross is not a rejection of the created world or a flight away from it, but rather its salvation. Paul writes that creation “shall be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God” (Rom. 8:21). Beyond the Second Coming lies cosmic restoration, a New Heaven and a New Earth, “wherein dwelleth righteousness” (2 Pet. 3:13). To this goal, the laws of Israel bore eloquent and practical witness. Early Colonial America honored this restitution model and a major step towards restoring the Republic today would be to once again, focus on the victims’ rights and Biblical restitution.

©2011 Off the Grid News

For Further Reading: Eastern State Penitentiary <https://easternstate.org/learn/research-library/history> Muriel Schmid, “The eye of God: Religious beliefs and punishment in early Nineteenth-century prison reform.” <https://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3664/is_200301/ai_n9199677/> Gary North, Victims’ Rights, The Biblical View of Civil Justice (Tyler, TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1990). Rousas J. Rushdoony, The Institutes of Biblical Law (N. p.: Craig Press, 1973). James B. Jordan, The Law of the Covenant, An Exposition of Exodus 21—23 (Tyler, TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1984). Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living