Jan. 5, 2017

January offers us a time for reflection and prediction. For centuries, people looked to the stars for signs of what is to come, and winter offers many opportunities for stargazing.

As we begin a new year, perhaps it is wise to consider not only the beauty of the sky but also the destructive power it holds.

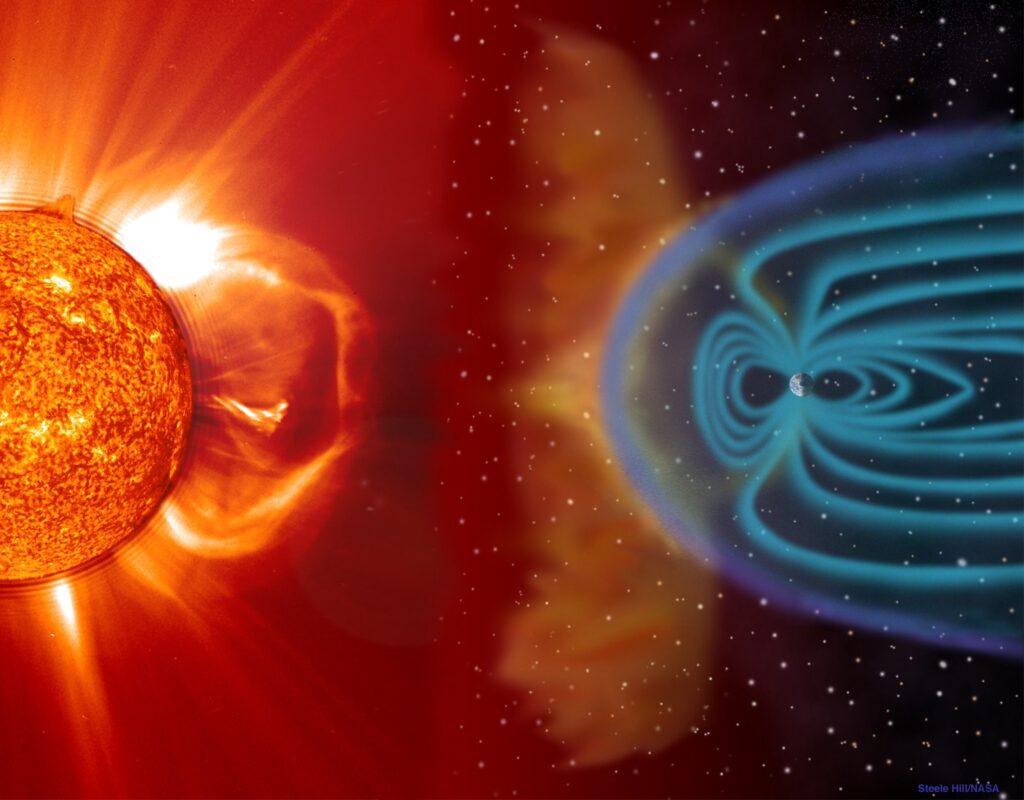

Astronomers pay particularly close attention to solar flares, which are sudden, intense and rapid variations in the sun’s brightness. These fairly common occurrences happen when magnetic energy that has built up in the solar atmosphere suddenly releases.

A solar flare contains high-energy photons and particles that are equivalent to millions of 100-megaton hydrogen bombs exploding at once. While regular solar flares are not a danger to Earth, extreme events, or solar storms, could be catastrophic to our way of life.

Are You Prepared For A Long-Term Blackout? Get Backup Electricity Today!

In fact, according to a study published in the journal Space Weather in 2012, there is a 12 percent chance (or, one in eight chance) that Earth will experience a catastrophic solar event within the next decade. This “megaflare” could disrupt or destroy modern technology, causing trillions of dollars’ worth of damage from which it could take many years to recover.

Space physicist Pete Riley made the prediction in the study by examining historical data and then making comparisons between the sizes and occurrences of solar flares.

Scientists have discovered that the sun goes through 11-year cycles of activity. During the solar maximum phase, the sun is covered with sunspots, and huge magnetic whirlwinds frequently erupt from its surface. Although it is rare, sometimes these flares burst away from the sun, sending massive amounts of charged particles into space.

The last recorded megaflare occurred in September 1859. Known as the Carrington Event, this enormous solar flare is named for astronomer Richard Carrington, who recorded his observations of the huge solar storm.

Carrington observed an enormous flare erupt from the sun’s surface that sent a particle stream toward Earth at a rate that exceeded 4 million miles per hour. These highly charged particles created breathtaking lights, or auroras, that were visible as far south as the Caribbean.

The New York Times in 1859 reported that New Yorkers gathered to watch “the heavens … arrayed in a drapery more gorgeous than they have been for years.”

Although the lights were indeed beautiful, the Carrington Event caused all kinds of disruption to 19th century communication systems. Telegraph stations caught on fire, and communication outages occurred on a scale never seen before.

In 1989, a geomagnetic storm – not as powerful as the Carrington Event — caused Canada’s Hydro-Quebec power grid to fail, leaving millions of people without power for up to nine hours. A similar storm today would have much more technology to disrupt, and the results would be catastrophic.

Be Prepared: Get The Ultimate In Portable Backup Power!

A megastorm on the scale of the Carrington Event could damage or destroy electrical power grids, disrupt GPS satellites and put a stop to Internet and radio communication.

According to a 2008 report from the National Research Council (NRC), a Carrington-like event could cost up to $2 trillion of damage within a year, and full recovery could take up to a decade.

The NRC report stated that, in addition to communication disruption, the event would adversely affect all aspects of modern life, including transportation, financial systems, government services. In turn, the distribution of water, food and medications would be halted.

In the conclusion of his 2012 report, Riley maintained that it is his hope that his prediction would be useful in building an “infrastructure that can withstand such an event.”

“Since the event occurred only 150 years ago, it is a constant reminder that a similar event could reoccur any day,” Riley wrote.

As we begin a New Year, it would be well if we took his advice.

Do you believe America is prepared for a Carrington-type event? Share your thoughts in the section below:

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living