If it weren’t for bad luck, some folks would have no luck all. But these folks often seem to have a deep-seated determination that drives them through the rough spots. One such determined fellow of the past was Ernest Shackleton. As an Antarctic explorer, his survival story – one of the most incredible in recorded history — can teach us all a bit about the grit it takes to get out of a serious pinch.

Ernest Shackleton was born an Anglo Irishman in 1874 and was raised in bustling London during the height of English imperialism. Bursting with energy and enthusiasm, at a young age Shackleton knew a life of adventure waited for him, as he dreamed of far-off lands and watched the sailing ships return from their exotic journeys. He became a certified master mariner, an Antarctic explorer, secretary of the Scottish geographical society, and made an attempt at English Parliament — all before his 30th birthday. To say the young boy from London had ambition, with the drive to match it, would be an understatement.

As Shackleton grew he was pestered by an underlying determination to achieve some sort of notoriety. At first his goal was to become the first to lead an expedition to the South Pole. Despite his best efforts he was unsuccessful in several attempts, and Roland Amundsen would become the first recorded human to stand on our most southern point. With the prestige of that journey evaporated, Shackleton shifted course and set a new goal: to become the first recorded man to cross the Antarctic continent.

Crazy Gadget Makes Every Window A Cell Phone Solar Charger

You can imagine how daunting this challenge would have been. He guessed the journey to be roughly 1,800 miles – 1,800 miles across the desolate, frozen, wind-swept, nothingness of Antarctica. Not only that, but he planned to start this expedition in the Weddell sea, a body of water generally unexplored at the time. In fact, much of the expedition would be through places the maps simply left blank. Heap on the added challenge of exploring a place where the record low is -128 degree Fahrenheit, and it becomes clear he was willing to risk everything. (He recorded temperatures of -23 – although it undoubtedly was colder at times.)

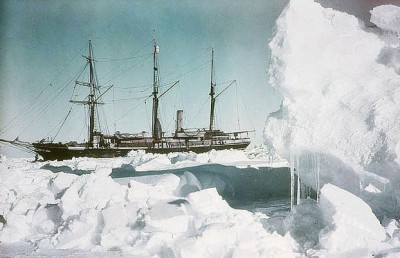

Despite the odds against an expedition, in 1913 Shackleton sorted through 5,000 applications to select the 28 men he believed would help achieve his goals. The group, a mix of experienced sailors, adventurers and greenhorns, set to sea aboard The Endurance on Aug. 8, 1914. As the unquestioned leader of the group Shackleton — or “The Boss” to his men — ran a tight ship. He believed in order and the necessity of routines to help the atmosphere and environment of the expedition. From the stories, The Boss had an intuitive way of leading men. This trait would be tested to its fullest potential in the coming months. The voyage went smoothly across the Atlantic and on Dec. 5, 1914, The Endurance and her crew pushed off from their last supply point at South Georgia island for the Weddell sea to begin their Antarctic exploration, looking to take advantage of the summer in Antarctica, which runs from late December through March. Little did they know, though, about the hardships awaiting.

As The Endurance moved south into the Weddell sea they began to encounter especially thick sea ice. The ship and her crew pushed on, slowly picking their way through the ice pack to open water. Ever so slowly the routes of escape grew less and less. Before long, The Endurance was surrounded by ice in all directions. Try as they might, the ship could not break through. Men were put to work trying to clear a path through the ice with saws and pick axes, but to no avail. By Jan. 19, 1915, it was becoming clear to The Boss the ship was stuck. A month later in his journal Shackleton noted, “The Endurance was confined for the winter …Where will the vagrant winds and currents carry the ship during the long winter months that await us?” Seems like the kind of uncertainty that can be a bit unsettling.

Story continues below video

At that point, all the men could do was sit and wait. The men were kept busy by cleaning the ship and performing regular chores. They also passed the time playing improvised soccer games and other forms of impromptu entertainment. Several of the men spent a good deal of time with the expedition’s sled dogs, which had been brought along the anticipated overland journey. All-in-all, the men made the best of a bad situation and spirits were as high as could be expected. This resolve would soon be tested by the ferocious elements surrounding them.

In July of 1915 the ship was becoming increasingly stressed by pressure from the surrounding ice. It moaned and creaked. Over the next few months, The Endurance would slowly crumble before the men’s very eyes. By October, the boat had nearly tipped completely sideways. It was becoming increasingly unsafe for the men to stay aboard and on Oct. 27, 1915, the order was given to abandon ship. There, on the floating sea ice, the men unloaded their gear, dogs and necessities to establish Ocean Camp, surrounding their disintegrating ship. In the sub-zero temperatures and gusting winds of 70 mph they could only watch as their ship was reduced to splinters.

New 4-Ounce Solar Survival Lantern Never Needs Batteries!

“It is hard to write what I feel,” read the journal entry of Shackleton. In the middle of an unexplored sea, floating haphazardly on ice no less, the group had just lost their ship.

By this point, the men had consumed nearly all of their food supplies, and the seals and penguins they hunted had vanished. Not only that, but they had determined that the ship has drifted over 1,100 miles trapped in the ice. Off course, food deprived, cold, and without communication or a boat, the crew could only do their best to ensure their continued survival. All of the dangers the men accepted when volunteering for the voyage were becoming more and more real. Nearly a year after being frozen in, the men had lost nearly everything and their odds of getting off the ice during the second year looked bleak.

That changed, however, by April of 1916. Incredibly, the winds had pushed the men within sight of Elephant Island, which lies on the extreme north edge of the Weddell sea. Just before The Endeavour sank, the men had managed to retrieve two of the lifeboats on the vessel. Although the boats were necessarily small, they offered the advantage of being able to be pulled around on top of the ice. Seeing some open water and an opportunity, Shackleton ordered the men to take to the boats and head for the island. In high spirits they landed and pitched camp. It was the first time the men had set foot on dry land in 497 days.

The celebration was short lived, though, as The Boss realized they were not out of the woods yet. The pack ice once again began closing in, and with no way to reach the outside world Shackleton made what likely was one of the most gut-wrenching decisions of his life. He decided to take a small crew and set sail for South Georgia Island, some 800 miles away. The ocean they had to cross contained some of the most violent waters in the world, and they fully expected to encounter 50-feet waves, ice cold water, and winds of 70 mph or more. And they were going to try it on a 22-food lifeboat called the James Caird. It had to feel like a suicide mission, but what ensued will go down as one of the greatest small boat journeys of all time.

Nearly immediately, the rough waves spilled over the sides, soaking the six men and their equipment. Clothes, sleeping bags and all other aspects of their gear became saturated with the freezing ocean water. For days on end, the small crew sailed on, soaked to the bone and battling strong winds and sleep deprivation. As ice built up over a foot thick on the boat itself, steering and balancing the small boat became a continuous chore. Although the elements tested the men to their core, their biggest threat came from the water itself.

In the middle of a particularly rough stretch of water Shackleton called out to the men that the sky was clearing ahead. Except that it wasn’t. Shackleton wrote:

In the middle of a particularly rough stretch of water Shackleton called out to the men that the sky was clearing ahead. Except that it wasn’t. Shackleton wrote:

I called to the other men that the sky was clearing, and then a moment later I realized that what I had seen was not a rift in the clouds but the white crest of an enormous wave.

During twenty-six years’ experience of the ocean in all its moods I had not encountered a wave so gigantic.

It was a mighty upheaval of the ocean, a thing quite apart from the big white-capped seas that had been our tireless enemies for many days. I shouted ‘For God’s sake, hold on! It’s got us.’ Then came a moment of suspense that seemed drawn out into hours. White surged the foam of the breaking sea around us. We felt our boat lifted and flung forward like a cork in breaking surf. We were in a seething chaos of tortured water; but somehow the boat lived through it, half full of water, sagging to the dead weight and shuddering under the blow. We baled with the energy of men fighting for life, flinging the water over the sides with every receptacle that came to our hands, and after ten minutes of uncertainty we felt the boat renew her life beneath us

With no time to waste, the crew pushed onward into the unknown. In a stroke of fortune, the crew of the James Caird managed to locate South Georgia island a harrowing 14 days after leaving Elephant Island. Bedraggled, frostbitten, sleep deprived and water logged, the small crew put ashore on a desolate shore. Shackleton knew the location of a whaling station on the island, but getting there would be a challenge. Not only were the men cold, worn down and exhausted, but the country between their landing location and the whaling station was once again blank on the map. If The Boss was to get to the station and save his crew, he would once again need to risk life and limb in order to do so.

Paratrooper: The Survival Water Filter That Fits In Your POCKET!

With two of the men in bad shape, Shackleton left one man behind to tend to their needs and he along with two other fellows embarked across the glaciers and rocky mountains of South Georgia Island. At one point the three men had to huddle together for body warmth simply to stay alive. Shackleton feared they would die if they slept, so they marched on without rest. It took the feeble group five days to cover the distance between their landing area and the whaling station. They were taken in by the station and given some very basic comforts, including a bath, shave and rest in a warm and dry bed.

True to his leadership reputation, The Boss wasted no time in setting out to rescue his two stranded parties of men. The sick men with the James Caird were fetched rather easily, but the 22 men on Elephant Island would pose a different story altogether. It would take the help of multiple governments and four ships to finally reach the stranded men on the desolate island. It was Aug. 30, 1916, when Shackleton finally gained sight of the men he had departed from some four months prior. It had been 634 days since the crew had initially headed into the unforgiving Antarctic waters — 634 days of frigid cold, wind and uncertainty. Amazingly, they all were still alive.

The legendary Shackleton Antarctic expedition was fortunate in that not a single man was lost. The story highlights the absolute tenacity of the human spirit and underscores what a person can endure. Not only that, but lessons from Shackleton’s leadership during the expedition may teach us about handling ourselves in seemingly hopeless situations. The story of Ernest Shackleton is one for the ages.

Bibliography

Bio.com Editors. (2016, Feb. 3). Ernest Shackleton. Retrieved Dec. 7, 2016, from The Biography.com website : https://www.biography.com/people/ernest-shackleton-9480091#synopsis

Buleen, C. (2016, Dec. 7). Average Temperatue of Antarctica. Retrieved Dec. 7, 2016, from USA Today.com: https://traveltips.usatoday.com/average-temperature-antarctica-13726.html

Cool Antarctica. (2016, Dec. 7). Shackleton Endurance Expedition. Retrieved Dec. 7, 2016, from Cool Antarctica: https://www.coolantarctica.com/Antarctica%20fact%20file/History/Shackleton-Endurance-Trans-Antarctic_expedition.php

South-Pole.com. (2016, Dec. 7). The Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1914-1917. Retrieved Dec. 7, 2016, from South-Pole.com: https://www.south-pole.com/p0000098.htm

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living