… A vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser; a misogynistic, homophobic, racist, infanticidal, genocidal, filicidal, pestilential, megalomaniacal, sadomasochistic, capriciously malevolent bully.

—Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (2008)

A three year old child may slap its father in his face only because the father holds it up on his knee.

—Cornelius Van Til, Toward a Reformed Apologetic (1972)

The Charge of Genocide

The word genocide is a modern one. It was coined in 1944 by Raphael Lemkin, a brilliant legal scholar originally from Poland, but Jewish by descent. The word literally means “killing a tribe.” Lemkin’s first definition was narrow: “the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group.” He quickly enlarged it to include “a coordinated plan…aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.” He included within his definition attacks on culture, language, religion, and social and political institutions. Lemkin’s work grew out of his familiarity with the Turkish slaughter of Armenian Christians during the First World War and the Simele massacre of Christian Assyrians in Iraq in1933. In his most important work, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe (1944), Lemkin analyzed the legal policies and procedures that Nazi Germany put in place to begin the work of genocide in its occupied territories.

Today there are those who charge the God of Scripture with genocide. God had ordered Israel to destroy completely the inhabitants of Canaan—to “save alive nothing that breatheth”; to “utterly destroy” the people of Canaan; to “show no mercy” (Deut. 20:16-17; 7:2). Was this genocide or something else? Why was God so wholesale?

What God Actually Commanded

The first time God addressed the matter, His concern wasn’t the extermination of the Canaanites. Rather, He promised to drive them out of the Land. He promised to use hornets as well as Israel’s armies (cf. Deut. 7:20).

And I will send hornets before thee, which shall drive out the Hivite, the Canaanite, and the Hittite, from before thee. I will not drive them out from before thee in one year; lest the land become desolate, and the beast of the field multiply against thee. By little and little I will drive them out from before thee, until thou be increased, and inherit the land. And I will set thy bounds from the Red sea even unto the sea of the Philistines, and from the desert unto the river: for I will deliver the inhabitants of the land into your hand; and thou shalt drive them out before thee (Ex. 23:28-33; cf. Deut. 7:12-26).

Throughout later passages, this emphasis reoccurs (cf. Duet. 4:38; Josh. 3:10; 13:6; 17:8; 23:5). God’s goal was to drive out those who held the Land and to grant possession of it to Israel according to His promises (Num. 33:52-56). God didn’t allow Israel to track down and destroy every single Canaanite they could find.

Still, those who remained, those who chose to fight the armies of Israel, did fall under the ban: they were dedicated to total destruction. In the end Israel killed a great many Canaanites. This was one important phase of Yahweh’s war against evil.

The Wars of Yahweh

This war began in the Garden of Eden. God’s curse physically altered the created order while His redemptive grace sustained it (Gen. 3). In the centuries that reached to the Flood, God’s Spirit strove with growing apostasy and bore prophetic witness to the judgment to come (Gen. 6; Jude 14-15). In the Flood God laid waste to the planet and destroyed a worldwide civilization (Gen. 7). He saved only eight souls out of millions, if not billions. At Babel He brought confusion to human language and scattered the peoples of the Earth (Gen. 11). On the plains of Jordan He turned Sodom and Gomorrah into flaming ruins (Gen. 19). At the Exodus He overthrew the might of Egypt and led His people to freedom (Ex. 14). Through most of this war, God’s people were called mainly to prophetic witness and faithful living. But the war against evil during those centuries was much more than a moral or intellectual struggle. Thousands and millions died under God’s judgment.

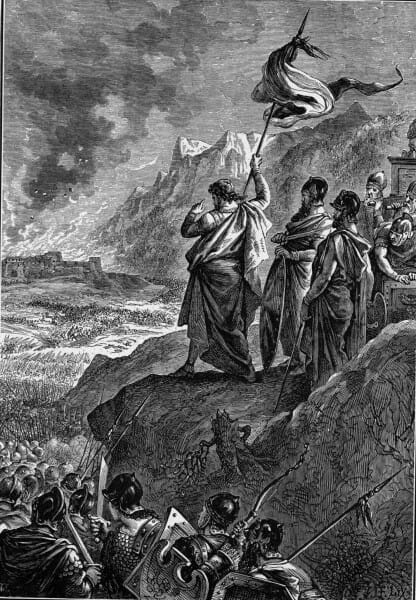

When Israel finally reached the borders of Canaan, the nature of the war changed. God put a sword in the hand of His people and ordered them to carry out His judgments. What Joshua began, the later judges continued. Then came Saul and David, who were also called to fight “the battles of the LORD” (1 Sam. 18:17; 25:28). But even as God called Israel to a military participation in His war against evil, He also began to direct His sanctions against Israel’s own disobedience. Both by prophetic witness and by the sword of alien armies, God fought against wickedness within the covenant community (1 and 2 Kings).

When Israel finally reached the borders of Canaan, the nature of the war changed. God put a sword in the hand of His people and ordered them to carry out His judgments. What Joshua began, the later judges continued. Then came Saul and David, who were also called to fight “the battles of the LORD” (1 Sam. 18:17; 25:28). But even as God called Israel to a military participation in His war against evil, He also began to direct His sanctions against Israel’s own disobedience. Both by prophetic witness and by the sword of alien armies, God fought against wickedness within the covenant community (1 and 2 Kings).

With the coming of Christ, Yahweh’s war came to focus in covenant redemption. The heart of God’s attack on evil was the death and resurrection of His Son. We now live a time of gospel-witness where Yahweh’s primary means of warfare is His Spirit-empowered word. This is not to say that God no longer brings judgment against evil, whether by natural catastrophe or by the sword of the magistrate. But the sword of the Spirit receives the overwhelming emphasis in the New Testament (Eph. 6:10-18; Heb. 4:12; Rev. 19:11-21; cf. 2 Cor. 10:3-6). Jesus rides through history slaying the nations with “the sword of His mouth.” One day, however, God’s longsuffering will come to an end. Judgment will fall. Jesus will return in power and glory to raise the dead and judge the world. God will sentence His enemies to a fiery hell. No more second chances.

Given all of this, it is a mistake to judge one phase of the war by what God does or doesn’t do in any other phase. God’s purposes in the conquest of Canaan were unique to that time and place, but they were most certainly His.

God’s Purposes

First among those purposes was the fulfillment of His promise to Abraham. That promise embraced, and laid the foundation for, the coming of the Messiah. God was preparing a people through whom His Son would enter the world and a place to which He would come. The promise of the Land was key to God’s plan of redemption. When Abraham inquired after details and asked for further assurance, God gave him a rough timetable. Abraham’s descendants would serve a foreign power for 400 years before they would inherit the Land. The reason: the iniquity of the Canaanites was not yet full. The tribes of Canaan received a gracious 400-year reprieve (Gen. 15:13-16).

But during those centuries the Canaanites continued in their sins. Their wickedness escalated. Their crimes against God included sorcery, incest, adultery, child sacrifice, sodomy, and bestiality (Deut. 18:9-14; Lev. 18:24-30). Not only did the Canaanites practice these things—they elevated them to the role of religious service (Deut. 12:31). Canaanite culture became a moral cancer that threatened all the nations round about them.

God, of course, was especially concerned with Israel. If God’s people didn’t drive out the Canaanites, they would eventually intermarry with them. Israel would be seduced into worshipping the Canaanite fertility deities (Deut. 7:1-4; 20:10-18). In the end, such apostasy would move God to destroy His own people and drive them out of the Land. It seems Israel could possess the Land only as long as she remained faithful to Yahweh (Deut. 11:22-23). In this sense, God did not play ethnic favorites—a lesson Israel was slow to learn (Matt. 3).

Is God Evil?

Yahweh’s critics—the new atheists among them—insist that God’s commands to destroy the Canaanites were evil. But what exactly do they mean? They could mean that God’s commands were inconsistent with His nature as it is revealed in the rest of Scripture. Or they could mean that God’s commands violate some standard of good and evil that is higher than God’s nature.

The first charge is an attempt to set God against Himself, or one part of Scripture against the rest. It is an attack on the consistency and infallibility of Scripture. As such, it is an indirect attack on the existence of God. If we accept the charge, we are left with a God who lacks internal coherence or a God who can’t reveal Himself properly; that is, one who is limited by His own creation. Such a God is no God at all.

The second charge sets God in the dock and accuses Him of wickedness. But we must ask His prosecutors, “What is the nature and basis of your accusation?” Or more plainly, “Whose law has God broken?” After a moment of confusion, the prosecutors may respond with something like: “It’s wrong to order the slaughter of thousands of men, women, and children. Everyone knows that!” A familiar but very lame answer.

First, it simply isn’t true. The Canaanites, for example, were firmly committed to human sacrifice, particularly child sacrifice, in the name of their gods. And even today there are tens of thousands of people who believe that killing children in the womb is a morally acceptable practice even though they acknowledge that those children are biologically (if not otherwise) human. Ask Hitler. Ask Mao. Ask Stalin. Nope, all men are not convinced that mass homicide is morally wrong. But even if we had such a consensus, we would still have to ask, “So what?” How does human opinion create a moral absolute that binds other humans, let alone the One who made those humans? Why should human opinion matter to God?

Any real moral criticism of God would have to rest on a standard above God, one by which He can and should be measured. But what could this standard be? Where could it come from? And why should God pay any attention to it?

Who God Is

The central issue here involves our understanding of who and what God really is. The God of Scripture presents Himself as self-existent in His Being and infinite in His perfections. He is the Creator of space, time, and matter and as such exists beyond their limitations and constraints. In comparison with Him, all the nations of the world are “less than nothing, and vanity” (Isa. 40:17). The distance between God and humanity is like that between the potter and his clay—infinite (Jer. 18:6; Rom. 9:20-21). And so there can be no other standards above or beyond God. God is absolute while creation is finite. Good and evil must be what He says they are. There is no higher court.

Of course, if there is no God, there are no absolutes, no right and wrong, no good and evil. Genocide, child sacrifice, racism, rape—all these things are morally neutral, for morality itself is a delusion. Good and evil become nonsense words. Whatever is, is “right.” God’s critics have no grounds for complaint beyond their emotional reflexes: they don’t like what He commands, just as some people don’t like broccoli. Yet the critics try to have it both ways. They borrow the biblical category of absolute right and wrong—something only an absolute God can provide—and then turn around and use it against God Himself. They are like the little girl who must sit on her father’s lap in order to slap his face.

Conclusion

Did Yahweh order genocide? Strictly speaking, no. God told His people to drive the inhabitants of Canaan out of the Promised Land and to kill any who would not leave. The issue was not their ethnicity, but their monstrous religion and their moral corruption.

Even so, God’s command came in the context of great mercy. God had a lot of patience with the folks who lived in Canaan—400 years and more. And even when judgment was at hand, God gave them proof of His power and wrath. They knew what He had done to Egypt (Josh. 2:10). They knew His promises to Israel. They could have fled; they could have repented. Rahab did (Heb. 11:31). They chose to defy and fight God instead.

In the end God’s judgment against Canaan wasn’t as severe as the Flood or as wholesale as the destruction of Sodom. In fact, the number of Canaanites who were killed is a small fraction of the number of lives God takes every year in our time—some 56 million. But the judgment against Canaan was a startling warning to mankind. Ezekiel tells us that God takes no pleasure in the death of the wicked (18:23; 33:11). But God does judge the wicked. He also honors His own holiness and justice by enforcing His laws. One day He will judge the world. In that day He will have no critics.

© 2012 Off the Grid News

For Further Reading:

Francis Schaeffer, Joshua and the Flow of Biblical History (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1975).

Rick Wade, “The Yahweh War and the Conquest of Canaan,” Bible.org, 2010. <https://bible.org/article/yahweh-war-and-conquest-canaan>

John Piper, “The Conquest of Canaan” November 7, 1981, <https://www.soundofgrace.com/piper81/112981m.htm>

Tremper Longman III, “The Case for Spiritual Continuity,” in Show Them No Mercy: 4 Views on Canaanite Genocide, ed. Stanley Gundry (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003).

Greg Bahnsen, Always Ready, Directions for Defending the Faith (Atlanta: American Vision/ Texarkana, AR: Covenant Media Foundation, 1996).

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living