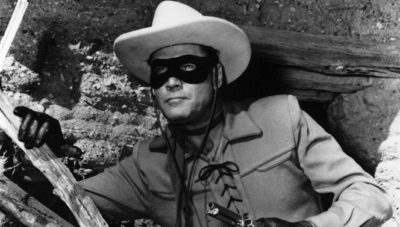

Who was that masked man?

— The Lone Ranger radio series (1933)

They call me Hawkeye. That’s from The Last of the Mohicans, the only book my father ever read.

—Dr. Benjamin Pierce, “A Full Rich Day,” M*A*S*H (1974)

The First “Hawkeye”

D. H. Lawrence wrote, “The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic and a killer. It has never yet melted” (Studies in Classic American Literature, 1923). He was writing about James Fenimore Cooper’s Leather Stocking Tales and particularly about the protagonist, Natty Bumppo — Hawkeye as we usually call him.

D. H. Lawrence wrote, “The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic and a killer. It has never yet melted” (Studies in Classic American Literature, 1923). He was writing about James Fenimore Cooper’s Leather Stocking Tales and particularly about the protagonist, Natty Bumppo — Hawkeye as we usually call him.

Hawkeye is the archetypical frontier hero. Born of white parents, he lives beyond white civilization among the Native American tribes. He is a scout, marksman, trapper and hunter. His religion is pretty informal … for him the whole earth is God’s temple, and he finds himself daily communing in spirit with “the infinite source of all he saw, felt and beheld” — and that “without the aid of forms and language.” He says he hates killing and objects even to killing animals without need, yet he does kill … a lot. The books are full of war and bloodshed, as you might expect.

OK, so let’s return to Lawrence’s main idea, his thesis: The American soul, and so the American hero, is hard, isolated by choice, stoic in his emotional responses, and violent unto death in his pursuit of “right” as he sees it. Hawkeye was really the first frontier hero. Legions of cowboys, scouts and sheriffs have followed, multiplied first by cheap novels and then by TV Westerns. Clint Eastwood is the archetype.

Romanticism and the Western

The Romanticism in Cooper is obvious, but it’s sort of Americanized Romanticism. Cooper places Nature above civilization, and man’s natural religious impulses above formal theology and worship. But Hawkeye still has a vague respect for the Christian faith and biblical ethics. He tries to live out the Golden Rule. He is chivalrous and kind. And in the end he helps forward the Westward expansion of Christian civilization.

This same Romanticism colored the heroes of television Westerns in the 50s and early 60s. Few family ties, no regular church attendance, skill with a gun and a horse, and a healthy respect for law and order, though accompanied by a ready willingness to play vigilante when lawful government failed.

And lawful civil government failed an awful lot in those days. How many corrupt bankers, ranchers, railroad men and politicians made their way through the countless episodes of Bonanza, The Big Valley, The Rifleman or the Lone Ranger?

The Lone Ranger is a good example here. He was one of America’s first masked heroes, a prototype of the masked mystery men and superheroes who would shortly follow. He was a Texas Ranger, but he gave that up to lead “the fight for law and order in the early West” without any legitimate authority. He was a vigilante, accountable to no one but himself.

As American Romanticism shifted through Realism into Existentialism, the parameters of the American hero shifted as well. He is still at odds with the Establishment, still free from the ties of family and church, and still handy with a gun. He is hard, often stoic and always detached. But the heart of gold is gone. He lives by his own rules. And though he usually takes down the bad guys, the collateral damage is substantial. No one lives happily ever after any more.

Total Depravity

Scripture rejects the Romantic view of human nature. Scripture says that man is fallen in Adam, guilty before God, and corrupt in his thoughts, emotions and choices. Man, by nature, has a wicked heart. Wealth and status may give one man more opportunity to express that wickedness than another, but these conditions don’t generate the sin. There is no virtue in poverty, rootlessness or a wilderness in existence, and no evil in position, wealth or the life of the city.

And, because of man’s inherent lawlessness, God has ordained civil government. “The powers that be are ordained of God,” Paul tells us (Rom. 13:1). For this reason, he says, “Let every soul be subject to the higher powers.” The NKJV and the ESV read, “governing authorities.” Anyone who resists the authority resists God’s ordinance or lawful arrangement (v. 2). Those who resist or rebel should expect to receive God’s judgment at the hands of the magistrate.

Peter says much the same thing:

Submit yourselves to every ordinance of man for the Lord’s sake: whether it be to the king, as supreme; or unto governors, as unto them that are sent by him for the punishment of evildoers, and for the praise of them that do well (1 Pet. 2:13-14).

For the most part, the apostles expected citizens to obey the civil authorities as a matter of faith and practicality.

Lesser Magistrates

But what if the magistrate himself is corrupt? What if he is lawless and criminal in his conduct? Scripture is well aware that such a situation is possible, if not likely. The men and women who serve in civil office, in the courts, or as police officers are sinners. It is likely that some, perhaps many, will abuse their power and authority.

John Calvin

Scripture, mostly by example, presents us with the doctrine of lesser magistrates or coordinate magistrates. Calvin touched on the doctrine in the final chapter of his Institutes (1536), but it was developed more fully in the Huguenot tract, A Defence of Liberty Against Tyrants (1579) and Samuel Rutherford’s Lex Rex (1644). The doctrine is this:

God has ordained many coordinate authorities within civil society — lords, kings, judges, mayors, senators, governors, etc. He entrusts them all with the authority to enforce His law. When any one of them violates that trust and rebels against the law of God, it is proper, even needful, for the other magistrates to resist his lawlessness and remove him from office. In doing this, they may enlist the help of those citizens who will stand with them. Those citizens may, under the authority of these “coordinate” magistrates, form a militia or army and take up arms against the lawless ruler and his forces. The English Civil Wars and the American Revolution are both examples of this doctrine in application.

We also see this doctrine played out repeatedly in the book of Judges and in certain episodes in the life of David before he became king. We see it in the New Testament in a less violent version when Paul repeatedly exercises his rights as a Roman citizen to rescue himself and his ministry from corrupt bureaucrats and officials. What Scripture doesn’t approve of is the autonomous rebel and assassin. David dealt with such men more than once (2 Sam. 1 & 4). He usually executed them.

Self-Defense

This brings us to the issue of lawful self-defense. There is one passage in the Law that directly addresses this: “If the thief is found breaking in, and he is struck so that he dies, there shall be no guilt for his bloodshed” (Ex. 22:2, NKJV). The next verse qualifies this: “If the sun has risen on him, there shall be guilt for his bloodshed.” In other words, if there’s an intruder in my home in the middle of the night, I have the right to shoot him dead. I don’t know who he is and I don’t know if he’s armed or not. He’s a potential danger, possibly a fatal one, to my family. I have God’s permission to defend my home with deadly force. The same permission doesn’t necessarily extend to the garage or barn.

This brings us to the issue of lawful self-defense. There is one passage in the Law that directly addresses this: “If the thief is found breaking in, and he is struck so that he dies, there shall be no guilt for his bloodshed” (Ex. 22:2, NKJV). The next verse qualifies this: “If the sun has risen on him, there shall be guilt for his bloodshed.” In other words, if there’s an intruder in my home in the middle of the night, I have the right to shoot him dead. I don’t know who he is and I don’t know if he’s armed or not. He’s a potential danger, possibly a fatal one, to my family. I have God’s permission to defend my home with deadly force. The same permission doesn’t necessarily extend to the garage or barn.

On the other hand, if it’s the middle of the day, if my family’s not in the house, if can see clearly that he’s not armed or if I can escape safely, then I can’t kill him. If I can see him in broad daylight, then I should report him to the proper authorities. Now, of course, if I see that he is armed and leveling his .45 at me, then I can fire. (Maybe even empty the clip.) American criminal law has observed these same basic principles for years.

Vigilantes: Conclusion

Nothing here gives an autonomous individual the right to track down law breakers or in any other way assume the duties and authorities of the local police or the courts. And certainly nothing here gives the ordinary citizen the right to use deadly force against officers of the law unless innocent life is really and immediately on the line and the citizen in question is ready to answer before a jury of his peers for his actions.

The pulp mystery men of the 30s and the costumed superheroes who followed were in most cases lawless vigilantes. Both Batman and Superman, for example, were initially at odds with the cops, and today’s Batman still is, I suppose. They, of course, all have something else in common … they were all fictional.

It is a Romantic and hugely juvenile mistake to confuse the actions of comic book vigilantes with the biblical right of self-defense or the broader doctrine of lawful resistance to tyranny. It is a worse mistake to think that revolution and anarchy can change society for the better. Lawlessness breeds lawlessness. Assassination brings retaliation. Anarchy leads to tyranny. Only the Gospel of Jesus Christ can effectively deal with human sin and create a law-abiding culture.

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living