“Sister,” she said, “What’s wrong? I mean about me…. Why do they call me the Accursed?”

—Psyche in C. S. Lewis’s Til We Have Faces (1956)

“It is expedient for us, that one man should die for the people, and that the whole nation perish not.”

—Caiaphas, the Jewish High Priest, AD 30

Scapegoats and Mimetic Theory

The idea of a scapegoat comes from the rites of Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement described in Leviticus 16. The original scapegoat was an animal that symbolically bore away the sins of God’s people into the wilderness. Today the word is used more broadly to describe those who are blamed and punished for the crimes or failures of the larger community. The attack on the scapegoat may range from simple snubbing to wholesale genocide.

At present, any discussion of scapegoats and scapegoating must include some reference to the work of René Girard (b. 1923), a Roman Catholic literary critic, anthropologist, and philosopher. His relevant works include Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1987), The Scapegoat (1986), and I See Satan Fall Like Lightning (2001).

Girard begins with a discussion of violence. He sees the roots of violence in desire. According to Girard, men learn desire in the context of the community and imitate the desires of others (mimesis). Men learn to want what their neighbors and role models want or have. Often men will want the same thing—the same object, honor, or position. This mimetic desire leads to wide-scale conflict and social upheaval. When the conflict is about to boil over and rend the fabric of society (a mimetic crisis), the community fastens on a substitutionary victim. This victim becomes the community’s scapegoat.

Girard begins with a discussion of violence. He sees the roots of violence in desire. According to Girard, men learn desire in the context of the community and imitate the desires of others (mimesis). Men learn to want what their neighbors and role models want or have. Often men will want the same thing—the same object, honor, or position. This mimetic desire leads to wide-scale conflict and social upheaval. When the conflict is about to boil over and rend the fabric of society (a mimetic crisis), the community fastens on a substitutionary victim. This victim becomes the community’s scapegoat.

The scapegoat will be chosen from the marginalized within the community. He/She (or a group) may come from the poor or the rich, from the handicapped or the ostracized. In any case, the victim will be marked by something easy to see. The victim will be obviously an outsider. The charges made against the victim are always the same: He has attacked or polluted that which is dearest to the life of the community (the throne, the temple, the family, our money) and has committed sacrilege against what the culture agrees is holy. The community, in a mimetic frenzy, turns on the victim. All against all becomes all against one. Self-deceived and self-righteous, the community destroys their scapegoat and does so with an almost clear conscience. The destruction of the scapegoat is cathartic. Theoretically, it restores harmony and solidarity to the community and enables it to move forward. The community, in effect, is born again. (One has to wonder what group will take the “scapegoat hit” for the coming economic collapse in America.)

But, oddly enough, there may be one more step. The community may realize after the fact that their victim has become their savior. The Accursed One has become the Holy One. The crowd may then accept the murdered victim as a resurrected god. Girard goes on to interpret the myths of the ancient world in terms of this scapegoat sociology. The great myths, he argues, mask the violence of a “founding murder,” the destruction and then deification of a scapegoat sometime in the historic past. He cites the myths of Balder, Dionysius, and the Aztec sun god as examples. Gerard doesn’t include Christ on his list, however.

Girard and Christianity

Girard believes that Christianity is unique among the religions of the world. While he freely admits that Christianity bears the outward form of a myth—the rejected Outsider dies at the hand of the envious crowd only to be resurrected and deified—he notes in it two major deviations from mythic religion. First, Christianity insists that Jesus was, in fact, innocent. The gospels don’t side with the crowd. Rather, they insist that those who killed Him were murderers. Second, God raised Jesus from the dead as objective evidence of His innocence and of the futility of violence. Girard sees Christianity as a rejection of mimetic desire and violence. He believes that its unique and defining characteristic, its absolute value, is compassion for the victim. For God in Christ became a victim, and in the gospel He calls us away from the contagion of violence. He calls us to love.

Some Criticism

Certainly Girard’s work is innovative and suggestive, but it is not without its flaws. Girard seems too ready to cram any social phenomenon that will fit into the mold of his mimetic theories. But similarity doesn’t guarantee identity. Something that looks like a group murder might be just the opposite. Think, for instance, of a surgical team plunging scalpels, needles, and tubes into a patient’s body. Think of the confusion, pain, and violence that surround the operating table. Or, on a different tack, we can ask what Girard would say about the story of Esther? Was Haman merely another scapegoat set upon by envious Jews? The story seems to fit Girard’s pattern.

The most serious complaint we can level at Girard, however, is his faulty view of the atonement. While Girard rightly sees Jesus as the innocent Victim of the crowd, he fails to understand the true nature of Jesus’ sacrifice. He can’t accept the Father’s role in the sacrifice of His Son. Yet Scripture is speaking of God the Father when it says, “Yet it pleased the LORD to bruise him; he hath put him to grief…thou shalt make his soul an offering for sin” (Isa. 53:10). The Father made His Son a sin offering. Judgment, violence, and wrath aren’t foreign to the nature of God in an absolute sense. God’s justice, His holy nature, demands the death of the law-breaker. God punishes sinners in hell. And yet this same God unilaterally provided atonement for sin through the death of His Son, His Messiah. And it is to this gospel message that the original scapegoat rite actually pointed.

The Day of Atonement

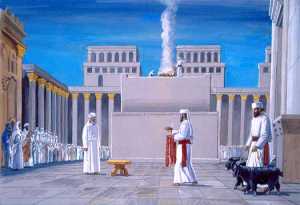

Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, was one of the chief holy days for ancient Israel. It was the only day of the year when anyone could enter the Holy of Holies, the inmost sanctuary of the Tabernacle or Temple. It was the day the high priest came into God’s presence with blood to reconcile Yahweh to His people.

Yom Kippur fell on the tenth day of Tishri, an autumnal month roughly equivalent to our late September and early October. Tishri was the seventh month of the religious calendar, but the first of the civil calendar. It marked the completion and climax of Israel’s seven-month liturgical cycle, and its first day, Rosh Hashanah, was New Year’s Day and a memorial of the original creation.

The rites of Yom Kippur had reference to the Tabernacle and later to the Temple in Jerusalem. Because God’s House was a representation of His covenant people, the sins of His people symbolically polluted and defiled that House. If these pollutions weren’t dealt with, the House would become so abominable that God would leave it altogether and surrender it to the Gentiles for total destruction. The atonement rites cleansed God’s House of ritual defilement so that Yahweh would be content to live in the midst of His people for another year. Of course, the annual repetition of the rites suggested their temporary character: They pictured a greater problem and ultimately a greater solution than the blood of bulls and goats (Heb. 9—10).

The Sprinkling of the Blood

The atonement ritual was the responsibility of the high priest. First, he chose two goats and cast lots between them. One would be the scapegoat; the other, a sin offering. The high priest had to offer two sin offerings— a bull for himself and his family and the goat for the people generally. He brought the blood of each sacrifice through the Holy Place, past the inner veil, and into the Holy of Holies. There he sprinkled the blood upon the mercy seat that covered the Ark of the Covenant. Within the Ark were the Tables of Stone, the Law that Moses had received on Mt. Sinai. Above the mercy seat, enthroned above its stylized cherubim, was the Shekinah glory, the visible manifestation of God’s Presence. The mercy seat thus lay between the Presence of God and the Law of God. God would look down from the glory cloud and see His broken Law through the intervening mercy seat. And when He looked, He saw atoning blood.

Propitiation

“Mercy seat” is an expression invented by William Tyndale (c. 1494-1536). The Greek Septuagint and the Epistle to the Hebrews call it the hilasterion, the place of propitiation (e.g., Heb. 9:5). The word propitiation has nearly dropped out of the Church’s vocabulary and is actually absent from many of the newer translations of Scripture. Propitiation speaks of turning away the wrath of God, of averting His anger. Of course, this implies that God is angry, angry with sin and angry with the sinner. Such a God is currently out of favor in both liberal and evangelical circles. Girard certainly has no room for this God in his system of interpretation. But this is the God of Leviticus and the God of Israel.

The Scapegoat

We come at last to the scapegoat itself. When the high priest had completed the liturgy of the sin offering (the bull and goat), he would turn to the remaining goat, the (e)scapegoat. (Tyndale invented this word, too.) The priest would put his hands on the goat’s head and confess over the goat all the sins of God’s people. Then the priest would surrender the goat to “a fit man” who would take the goat out into the wilderness. The goat symbolically carried the sins of God’s people out of sight and out of mind. This part of the atonement ceremonies was very public. Everyone would see the goat’s departure. Everyone would see the promise of God. The day that began with solemnity and affliction of the soul would end with great joy and gladness. God was content to tabernacle among men.

Conclusion

At the heart of the Christian gospel is blood atonement. God sacrificed His Son to satisfy the demands of His own justice so that He might save sinners from hell. Christ went to the cross for the glory of His Father and out of love for condemned sinners who needed a Redeemer. What Yom Kippur pictured in shadow, the gospels give us as history. Jesus is “the propitiation for our sins: and not for ours only, but also for the sins of the whole world” (1 John 2:2).

For Further Reading on Girard:

René Girard, The Scapegoat (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1986)

René Girard, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2001).

Douglas Wilson, “Money, Love, Desire—All in Girard, Man!”, November 05, 2007. <https://www.dougwils.brainfog.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4716%3AThe-Scapegoat&catid=111%3Aall-in-girard-man&Itemid=171>

For Further Reading on the Day of Atonement:

Philip H. Eveson, The Beauty of Holiness, Leviticus Simply Explained (Webster, NY: Evangelical Press, 2007).

G. J. Wenham, The Book of Leviticus (Grand Rapids: Wiliam B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1979).

Rousas J. Rushdoony, Politics of Guilt and Pity (Nutley, NJ: The Craig Press, 1970).

©2011 Off the Grid News

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living