They had the shadows, we have the substance.

—Matthew Henry on Colossians 1:17

The Ever Circling Years

In pagan religion, man helps sustain the cycles of Nature and perhaps the universe itself through ritualistic magic. The traditional magician’s formula is, “As below, so above.” For pagan worship, the microcosm always turns the macrocosm—the universe. Since for pagan thought and worship, history is cyclical, pagan rituals are especially bound to days, months, and years. Man must perform the same rituals every year, or every decade, or every century, in just the right way. The pagan calendar is an instruction manual and timetable for the magical ritual that sustains reality itself. If man fails in his rituals, the universe may collapse or go over the edge. Sometimes the required rituals are innocuous; sometimes they are terrifying. But always they are necessary. In this scheme, the universe depends upon man.

For Christianity, the observance of required days is an ethical matter. These days are a means to spiritual nourishment and discipline. On these days, God reveals Himself through His word and sacraments, He renews His covenant with His people, and He calls His people to respond with worship. As His people submit to this process, they grow in their sanctification, in faith and obedience, and God blesses them. But in reality, God doesn’t need us or our worship.

For Christianity, the observance of required days is an ethical matter. These days are a means to spiritual nourishment and discipline. On these days, God reveals Himself through His word and sacraments, He renews His covenant with His people, and He calls His people to respond with worship. As His people submit to this process, they grow in their sanctification, in faith and obedience, and God blesses them. But in reality, God doesn’t need us or our worship.

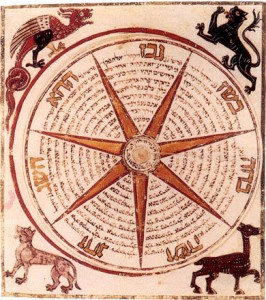

The Old Covenant had six major festivals besides the weekly sabbaths (Lev. 23). There were also new moons, sabbath years, and every fiftieth year, the Jubilee (1 Chron. 23:31; Lev. 25). From a biblical perspective, none of these festivals were magical and none had any ontological force in and of themselves. (None of the rites associated with these days ever moved or shaped the universe.) The rites that God ordained were revelation and promise, not magic or manipulation. Israel’s calendar emphasized God sovereignty and man’s responsibility, freedom, and authority under God.

Israel’s Worship and Liturgical Calendar

Israel’s worship and liturgical festivals ran through seven months, from spring to autumn. Each festival was a commentary on, and an expansion of, the weekly Sabbath. The Passover pointed back to the Exodus and forward to Israel’s final redemption from sin. The waving of the first fruits sheaf three days later spoke of resurrection for both the Representative and the whole. Fifty days later, Pentecost commemorated the giving of the Law and looked forward to the outpouring of the Spirit and the harvest of souls that would follow. The last three annual festivals fell in the seventh month: these were the Feast of Trumpets, the Day of Atonement, and the Feast of Tabernacles. The concentration of these three festivals in the seventh month emphasized its sabbatical nature.

The Feast of Trumpets introduced this sabbatical month and called God’s people to search and try their hearts. The Feast began on the 1st of Tishri, the day the world was born, and was New Year’s Day on the civil calendar. But it was also a picture of judgment to come, both within history and at its end. The blowing of trumpets was connected with God’s enthronement. Trumpets announced the coming of Yahweh, the blessed and terrible Day of the LORD.

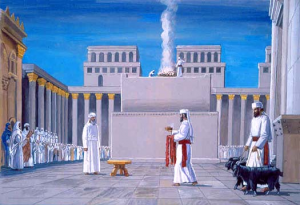

The Day of Atonement came ten days later. It was the only day in the year when the high priest could enter the Holy of Holies in the Tabernacle. There he would sprinkle sacrificial blood on the mercy seat that covered the Ark of the Covenant (Lev. 16). The blood was an archetypical propitiation for sin. That is, it was a type and image of the blood of Christ—a picture of His substitutionary death as true atonement for sin (1 Jn. 2:2). Its immediate effect was to “remind” God of His own promise to dwell in the midst of His people. But the ritual had to be done in faith. God couldn’t be deceived or manipulated by outward forms. Though Israel might cry, “The Temple of the LORD! The Temple of the LORD! The Temple of the LORD!”, God would only honor true faith in His covenant promises (Jer. 7:4).

The Day of Atonement came ten days later. It was the only day in the year when the high priest could enter the Holy of Holies in the Tabernacle. There he would sprinkle sacrificial blood on the mercy seat that covered the Ark of the Covenant (Lev. 16). The blood was an archetypical propitiation for sin. That is, it was a type and image of the blood of Christ—a picture of His substitutionary death as true atonement for sin (1 Jn. 2:2). Its immediate effect was to “remind” God of His own promise to dwell in the midst of His people. But the ritual had to be done in faith. God couldn’t be deceived or manipulated by outward forms. Though Israel might cry, “The Temple of the LORD! The Temple of the LORD! The Temple of the LORD!”, God would only honor true faith in His covenant promises (Jer. 7:4).

The Feast of Tabernacles was eight days long, from the 15th to the 22nd. It recalled Israel’s sojourn in the wilderness beneath the Glory Cloud. As the final harvest festival of the year, it pointed forward to the eschatological harvest of the Gentiles, the unification of all of God’s people in one Spirit-filled community. The seventy bulls offered during the week of the festival were a plea for God’s mercy toward the nations of the world (reckoned as seventy in Genesis 11). The Feast of Tabernacles was generally ignored throughout Israel’s history, but God brought it back into sharp focus during the Restoration Era, the time just before Jesus came to Earth (Neh. 8:14-17; Zech. 14:16-21).

The Sabbath and the Lord’s Day

The Old Covenant Sabbath was a memorial of things past, of creation and redemption, of divine election and special revelation. It was a prophecy of things to come, of a new age of the Spirit, of definitive atonement and final propitiation, of resurrection and judgment. It was a time to draw near to God, a time for judgment, a time for covenant renewal, and a time for worship. But under the Old Covenant, all these things were cast in shadows (Col. 2:16-17). The reality was hidden in pictures, and God’s people had to trust Him to fulfill His ends in ways they could not imagine. The gospel was, for the most part, still a mystery (Eph. 3:4-6).

The New Covenant picks up all of these sabbatical themes and places them in the full light of Christ’s resurrection. The New Covenant, however, has only one stated day for formal worship, the Lord’s Day. And it is named only once—in the first chapter of Revelation. The context of that naming is significant. It’s the first day of the week: the apostle John is in the Spirit (Rev. 1:10). In vision he sees Jesus, attired as a priest, thundering like the Glory Cloud, and walking in the midst of the churches. On the Lord’s Day, Jesus comes to meet with His people. He stands in their midst; He holds their messengers in His hand. He addresses each church in turn (ch. 2-3). He speaks through His angels (His messengers): He warns, exhorts, admonishes, and promises. His coming is judgment; that is, He comes to inspect His churches and to bless or reprimand based on what He finds. Then John is caught up to heaven, and he sees reality from God’s perspective: He sees the Church gathered about the throne of God, surrounded by angels, and worshipping the Lamb (ch. 4). The Book of Revelation continues as a worship service that has consequences for heaven and earth. And yet there is no magic. There is, rather, the fellowship of the sovereign God with His covenant people through the blood of the Lamb.

Conclusion

Going to church is not a lecture or a rally or entertainment. It is Judgment Day. Like the Old Covenant sabbaths, the Lord’s Day anticipates the great Day of the Yahweh. It is the Day of the LORD in miniature. Every Sunday we come into God’s presence and stand before Him for judgment. If we come through faith in Christ, we find assurance of pardon, encouragement and direction, the communication of grace and power, fellowship with Him at His Table, and a blessing and commission to return to our work of stewardship in the wider world. But if we come in presumption and spiritual pride, if we come in unbelief and without repentance, we find rebuke and chastisement (1 Cor. 11:27-32). We may even find death (1 Cor. 11:30). But there is nothing “magical” here. There is only personal interaction with a covenant-keeping God, who always honors those who seek Him in faith.

For Further Reading:

Gary North, Unholy Spirits, Occultism and New Age Humanism (Ft. Worth, TX: Dominion Press, 1986).

Gary North, The Sinai Strategy, Economics and the Ten Commandments (Tyler, TX: The Institute for Christian Economics, 1986).

Herbert Schlossberg, Idols for Destruction, Christian Faith and Its Confrontation with American Society (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1983).

David Chilton, Paradise Restored, A Biblical Theology of Dominion (Tyler, TX: Reconstruction Press, 1985).

David Chilton, The Days of Vengeance, An Exposition of the Book of Revelation (Ft. Worth, TX: Dominion Press, 1987).

James B. Jordan, Theses on Worship, Notes Toward the Reformation of Worship (Niceville, FL: Transfiguration Press, 1994).

©2012 Off the Grid News

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living