Sacrifice is commonly treated as a relic of man’s primitive past….

—Rousas J. Rushdoony (1992)

The bleeding Sacrifice in my behalf appears. —Charles Wesley (1742)

The Purpose of Sacrifice

Sociologists and anthropologists struggle with understanding and defining the rite of sacrifice. Is sacrifice religion or magic? Is it a bribe or a gift? It seems to function differently in every ancient culture and to work in each culture on different principles and for different ends. In the face of such confusion, Greek religious historian Marcel Detienne claims that there was no such thing as “sacrifice.” He considers it an invented category, a “category of yesterday’s thought.” In other words, sacrifice belonged only to the religious world of the Jewish and Christian Scriptures, a world that is obviously passé.

Still, most scholars continue to look for a lowest common denominator definition that will retain the category of sacrifice while still making it sociological useful. Perhaps sacrifice is simply a gift to some supernatural entity later to be named. Maybe it’s an original act of violence justified retroactively in the name of newly invented gods. Or perhaps sacrifice represents a hidden ethical quest. In “Stories of Sacrifice” (2011) John Milbank suggests “that what all societies have really been struggling to express is the necessity for moral self-sacrifice on the part of the individual for the sake of the law, so enabling the operation of the social group.” Sacrifice thus forms the ritual and psychological basis for ethics and so for community.

From a biblical perspective, we must say that Detienne was right in part. The biblical doctrine of sacrifice is unique. The biblical sacrifice is neither magic nor bribe. It is neither a contract payment nor a mere present. It is a covenant sacrament. All the sacrifices of the pagan world are departures from and corruptions of the biblical practice. And they are all wrong, howbeit in many different ways.

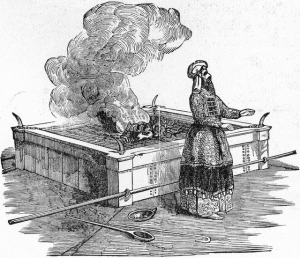

The Ritual of Sacrifice

After they left Sinai, Israel sacrificed at the Tabernacle, where God sat enthroned in the midst of His people. Each worshipper, whether man or woman, brought a sacrificial animal to the altar at the Tabernacle gate. The animal might be a young bull, a goat, or a sheep. The poor could bring pigeons or turtledoves. The worshipper would present the animal to God’s priest. Then the worshipper would place his hands on the animal’s head. This marked the animal as his substitute. He would then kill the animal himself. This was important. The worshipper was acknowledging that he was responsible for the death of this animal. It died because of his sins, not for any fault of its own. After this, the priest would take over. He would flay the animal, and then, depending on the precise nature of the sacrifice, he would burn some or all of its flesh on the altar and splash, sprinkle, or dab some of the animal’s blood on the sacrificial altar, the incense altar inside the Tabernacle, or the inner Tabernacle veil, the one that hung before the Holy of Holies.

After they left Sinai, Israel sacrificed at the Tabernacle, where God sat enthroned in the midst of His people. Each worshipper, whether man or woman, brought a sacrificial animal to the altar at the Tabernacle gate. The animal might be a young bull, a goat, or a sheep. The poor could bring pigeons or turtledoves. The worshipper would present the animal to God’s priest. Then the worshipper would place his hands on the animal’s head. This marked the animal as his substitute. He would then kill the animal himself. This was important. The worshipper was acknowledging that he was responsible for the death of this animal. It died because of his sins, not for any fault of its own. After this, the priest would take over. He would flay the animal, and then, depending on the precise nature of the sacrifice, he would burn some or all of its flesh on the altar and splash, sprinkle, or dab some of the animal’s blood on the sacrificial altar, the incense altar inside the Tabernacle, or the inner Tabernacle veil, the one that hung before the Holy of Holies.

There were actually five offerings described in the Levitical law (Lev. 1—7):

- In the ascension offering, the whole animal was consumed, with only the skin excepted. This offering underscored the worshipper’s complete dedication to Yahweh.

- In the grain or tribute offering, the worshipper presented flour, cakes, or wafers. This was the only bloodless sacrifice, but it always accompanied the ascension offering. It reminded the worshipper that all his work and all the labors of his hands were Yahweh’s too.

- The peace offering was for those who needed to pay a vow or those who simply wanted to rejoice in God’s goodness. In the peace offering, only a token of the flesh was consumed in the fire; the rest the worshipper shared in a communion meal with the officiating priest.

- The purification offering dealt with specific sins. Its purpose was to cleanse the Tabernacle of the moral contamination it symbolically acquired from the sins of the people so that God would continue to dwell with them. The sacrificial animal was determined by the role that the offender played in covenant life. The more central his position, the more expensive the sacrifice and the closer to God’s presence the priest sprinkled the sacrificial blood. The officiating priest ate some of the flesh to testify that God accepted the sacrifice and the penitent sinner.

- Finally, the reparation offering dealt with offenses against holy things, with sacrilege, and with the intrusion of the profane into the sacred. It generally involved restitution: the return of the original plus 20 percent of its value.

The primary focus of sacrifice was Messiah. Through His Messiah, God would provide atonement for the sins of His people (Isa. 53; Ps. 22). Messiah would be the ultimate sacrificial Lamb and His shed blood would be propitiation for sin. The worshipper who brought a sacrifice confessed that his hope was not in the slaughtered lamb or bull, but in the great Lamb of God, who was yet to come. In other words, Israel’s sacrificial system pointed beyond itself and therefore implicitly foreshadowed its own eventual demise (Heb. 10).

The primary focus of sacrifice was Messiah. Through His Messiah, God would provide atonement for the sins of His people (Isa. 53; Ps. 22). Messiah would be the ultimate sacrificial Lamb and His shed blood would be propitiation for sin. The worshipper who brought a sacrifice confessed that his hope was not in the slaughtered lamb or bull, but in the great Lamb of God, who was yet to come. In other words, Israel’s sacrificial system pointed beyond itself and therefore implicitly foreshadowed its own eventual demise (Heb. 10).

The Sociology of Sacrifice

Because blood sacrifice lay at the heart of Israel’s formal covenant with Yahweh, it has implications for far more than the doctrines of atonement and worship. Implicit in the Levitical system of sacrifice are principles that involve our understanding of sovereignty, law, and community.

First, through sacrifice the worshipper acknowledged the sovereignty of Yahweh over his person and life. The sacrifice was not a bribe or a contract payment. In laying his hands on the sacrificial animal, the worshipper identified himself with the animal, and in giving the animal to God, the worshipper gave himself to God. Though this was involved in all the Levitical offerings, it was especially underscored in the ascension offering. The worshipper gave the whole animal to God, and the flames consumed it wholly. The worshipper was no longer his own. His life was now circumscribed by divine law and “bound in a bundle of life with the LORD” (1 Sam. 25:29).

Second, biblical sacrifice demonstrated the legal and covenantal nature of God’s relationship with His people. God is just and holy. Transgression of His law offends His holy nature; His justice demands retribution. While we may rightly speak of a broken relationship that needs restoration, sacrifice spoke clearly to the issue of guilt as well. The sinner is legally guilty. He has broken God’s law, and he deserves punishment. Or put the other way around, God’s own nature requires that He punish those who break His laws. Sacrifice established the legal nature of grace, salvation, and covenant life, but it also established the death penalty as an inescapable reality.

Third, sacrifice portrayed the legality and necessity of covenantal representation and substitution. The sacrificial animal stood in the place of the worshipper and symbolically took his judgment. Here justice and mercy met. Mankind originally fell into sin and guilt through the representative act of a single man, Adam. Men and nations continued to receive judgment and blessing because of the representative acts of their covenantal leaders. And though the sacrificial laws placed a heavy responsibility on civil leaders, they placed an even greater responsibility on those who ministered God’s word and sacraments. Worship is more important than politics.

Fourth, sacrifice spoke of restoration. The worshipper didn’t simply escape just punishment. He was brought back into a right relationship with his Creator. This comes across most clearly in the purification offering and the peace offering. The first cleansed the Tabernacle so that Yahweh would dwell with His people in blessing. The second became a fellowship meal shared by the worshipper with Yahweh’s priest. Through His representative, God rejoiced to eat a meal with the forgiven sinner.

Fifth, the sacrificial ritual also spoke of sanctification. The Tabernacle, its veils, and altars were all splashed or sprinkled with blood. The Tabernacle represented God’s presence with His people. To cleanse the Tabernacle was to cleanse the congregation. God’s people were thus symbolically released from the pollution and power of sin, just as they were freed from its penalty. The sacrifice promised ethical transformation and Spiritual empowering to those who believed the promise.

Sixth, sacrifice pointed beyond sanctification to glorification. The sacrifice, with which the worshipper was identified, was taken into the holy fire (the glory of God) and transformed into smoke that rose to heaven. In sacrifice the world to come became a present reality. The New Jerusalem was sacramentally present.

Seventh, sacrifice was and is the foundation of true community. Only a people who have been befriended by God, who are at peace with God, and who can rejoice before Him, can be transparent and humble towards one another. Blood loyalty to Yahweh necessarily generates a covenant bond that embraces all those who have been touched by the blood. This is because they have all passed through the same baptism, and therefore they all eat of the same sacramental food. They together share a life of fellowship with their Savior and King.

Conclusion

The sacrifices on Israel’s altar spoke volumes. They spoke of a just and holy God, a gracious, covenant-keeping God, a God who sacrifices to save His people. The sacrifices also spoke of a new world order, one centered in the Person and work of Messiah. The sacrifices were wonderful and glorious. Their only fault: they were pictures and shadows. The Reality was yet to come.

For Further Reading: Gary North, Leviticus: An Economic Commentary (Tyler, TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1994). Peter J. Leithart, A House for My Name: A Survey of the Old Testament (Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2000). Vern Poythress, The Shadow of Christ in the Law of Moses (Brentwood, TN: Wolgemuth & Hyatt, Publishers, Inc., 1991). Rousas J. Rushdoony, The Institutes of Biblical Law, vol. 1 (N. p.: The Craig Press, 1973). Rousas J. Rushdoony, Law and Society: The Institutes of Biblical Law, vol. 2 (Vallecito, CA: Ross House Books, 1982).©2011 Off the Grid News

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living