In today’s modern world, it is easy to tell time. There are clocks on buildings, billboards, cell phones and microwave ovens. Then there’s the old-fashioned grandfather clock in the hallway.

But what if you didn’t have a watch? What would you do then?

And if you didn’t have a calendar, would you know when winter was coming? When it was the appropriate “time” to plant? To harvest? How old you are? How long would it take for you to “forget” to mark down a day or several days, or several weeks, thus obscuring even your age?

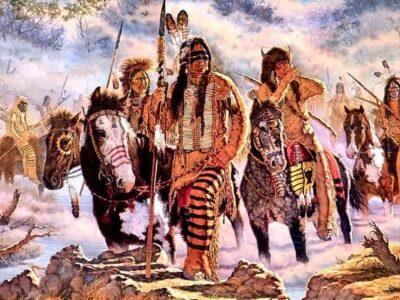

Native people had certain signs that they relied on and they actually had a very good sense of “time” — even though it differs from what we would consider time today.

White Man’s Time Clock

For many tribes, the clock – the one the Europeans used and brought to America — was a strange thing that was not easily understood. Some tribes thought that since the clock moved on its own and that it sometimes made sounds, it was a living thing.

Get The Essential Secrets Of The Most Savvy Survivalists In The World!

The simple truth here is that indigenous people considered time to be a part of the natural cycle of life. The belief was that there was a correct time or best time for everything and that nature itself would send the signal to let a person know when that was. A clock, divided into so many tiny fragments, seemed ridiculous and inconceivable to them. What difference could it make if one planted corn on this side of the 12 or that side of the 12?

A popular meme says that when an old native person was told about daylight saving time, he shook his head and said that only a white man would think he could cut off the bottom of a blanket, sew it to the top of a blanket, and then think he had a longer blanket.

Time Signals

Before European contact, indigenous people found that nature imparted a natural order and rhythm to their lives. Sunrise and sunset marked the typical day, with the noon sun being the dividing part between morning and afternoon.

Almost all tribes had some sort of marker for the spring/summer/fall/winter equinox. For the Pawnee, they knew that when the sun rose over a particular crest on Corn Mountain, it was time to hold their Thunder ceremony. The Bighorn medicine wheel told the Lakota when to travel to meet with others for their annual Sun Dance, which is held in and around the summer solstice.

Many tribes simply assigned names to certain seasons or months to keep track of how old a person was. The exact day was of less importance to native people than the time of the year. For example, according to the Lakota, if you were born in the time of trees popping, you were born sometime in late December through January. Native people felt this was distinction enough.

Native people also had a tendency to measure by nights, rather than by days. Indigenous people would say they traveled for “x” number of moons rather than by days or suns. Some tribes also used “moons” to indicate months. For example, March would be called the Moon of Sap Running by the Lenape.

Still other tribes marked their time through winter counts. Regardless if you were born in June or December, you were born in the “Winter of Four Crows Killed.” Usually some important event would mark the end of the year, which the entire year was named for. You could be born in May and you would still refer to your birthday as the Winter of Four Crows Killed.

Hunting, Planting and More

The natural cycles of nature also helped to organize task-based plans. For tribes who planted crops, they used signals such as the size of oak leaves to let them know that it was time to plant. The Crow tribes knew that when chokecherry trees blossomed, it was the right time to plant tobacco. Snow deeper than the ankle was a sign to most tribes that long-range hunts were finished for the year.

New Solar Oven Is So Fast It’s Been Dubbed “Mother Nature’s Microwave”

Tribes that planted crops often used that cycle as their means of telling time. For example, they might remember that they were born when the corn was gathered or that they were married with the flower buds of the squash.

Spring equinox compelled West coast people to travel to the sea to catch sardines or to gather shellfish. After a few weeks, they knew it was then time to move back inland to collect acorns, grasses and other nuts or seeds.

Water collection, or knowledge of where one could obtain water, was crucial to many Pueblo tribes. Many tribes stored water in clay pots and then buried them in the ground for later use. How would you know when it was time to collect water from the remaining pools if you did not know what season it was or how long it would be before the rains would come again? Most Pueblo tribes used a calendar stick to mark time. One person would mark off each sunrise on a stick, 30 days per stick. Each stick was saved until there were 13 sticks. Their lunar cycle was one of 13 months to a year. In this method, they knew, almost to the day, when the rains would start and how many sticks they had to make their water last.

Sometimes, it seems as if native people still run on “Indian time.” If you have ever attended a powwow and saw that the Grand Entry was supposed to occur at noon, but didn’t actually happen until 1:30, you have experienced “Indian time.” The hour or minute was, and in some cases still is, of little importance. Did the job get done properly? Then it was a job well-done — and done in perfect time.

Have you ever had to tell time without a watch? Share your tips in the section below:

Learn How To ‘Live Off The Land’ With Just Your Gun. Read More Here.

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living