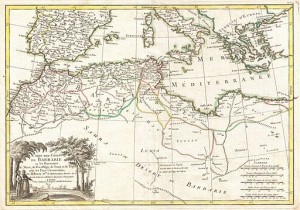

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a coalition of Muslim states in northern Africa (Tunis, Algeria, Morocco, and Tripoli) carried out a sustained military campaign directed against the Christian nations of western Europe, specifically England, Spain, France, and Denmark. Essentially, this conflict was a continuation of a struggle that had originated in the days of the Crusades, and the Barbary Powers, as the Muslim nations were called, were determined to avenge past outrages against their faith.

Unfortunately, American merchant vessels sailing the Atlantic were frequently caught in the crossfire of this conflict. Seeing no distinction between the old Christian nations of Western Europe and the young Christian nation from across the sea, the Barbary Powers attacked U.S. ships and abducted U.S. sailors with impunity. Seeking a remedy for this situation, President Washington sent envoys to negotiate a peace treaty with Muslim representatives. The Treaty of Tripoli, in which the Barbary Powers promised to stop their piratical activities against U.S. ships in return for financial tribute, was agreed upon by both sides and signed into law by the new American president, John Adams, in 1797. In the end this treaty proved to be a failure, and the U.S. Navy was eventually deployed to the region in order to subdue the fierce Barbary marauders.

Unfortunately, American merchant vessels sailing the Atlantic were frequently caught in the crossfire of this conflict. Seeing no distinction between the old Christian nations of Western Europe and the young Christian nation from across the sea, the Barbary Powers attacked U.S. ships and abducted U.S. sailors with impunity. Seeking a remedy for this situation, President Washington sent envoys to negotiate a peace treaty with Muslim representatives. The Treaty of Tripoli, in which the Barbary Powers promised to stop their piratical activities against U.S. ships in return for financial tribute, was agreed upon by both sides and signed into law by the new American president, John Adams, in 1797. In the end this treaty proved to be a failure, and the U.S. Navy was eventually deployed to the region in order to subdue the fierce Barbary marauders.

The conflict between the Muslim nations of northern Africa and the United States, called the First Barbary War, lasted from 1801 to 1805. This war has largely been forgotten now, but surprisingly the failed Treaty of Tripoli, which presumably should have been confined to some dusty, obscure government archive long ago, is still remembered and is still being quoted to this very day. This is because of one section of the document, Article XI, which contains one sentence that some have seized upon as proof that the Founding Fathers did not consider Christianity to be an important aspect of the new nation they had worked and fought so hard to create.

Christianity and the Founding of a Nation – Separating Myth from Reality

Here is the entire paragraph from which this sentence – or more accurately, part of a sentence – was extracted. As the reader would no doubt have been able to discern on his or her own, it is the very first clause of Article XI that has garnered so much attention:

“As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility of Musselmen [Muslims] and as the said States have never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.”

For reasons that are not always clear, a good portion of academia and certain parts of the media are quite hostile to the idea that religion has played any constructive role in the history of the United States, or in the history of the world in general. These people don’t deny that religion has been a factor in human society; rather, what they deny is that it has ever been a positive factor in human society, in either its daily functions or its progressive evolutionary development. For this crowd, religion and spirituality are based on irrational, reactionary impulses, and as such, religious belief is inimical to the functioning of a humane, logical culture – like the eminently rational subculture that supposedly exists within the hallowed halls of academia, for example.

It is easy to see why this view of religion has little tolerance for the suggestion that the Founding Fathers were motivated in their work in any way by Christian principles or beliefs. After all, the thinking goes, how could the authors of such amazing documents as the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights possibly have been motivated by something illogical and regressive like religious superstition? While the people responsible for these grand testaments to the sanctity of democracy and freedom may have paid lip service to their piety, this must have been done for reasons of politics more than anything else. For those who are attracted to this line of reasoning, discovering an official U.S. diplomatic document – and one drafted during the Washington Administration at that – which actually states that our government was “not in any sense founded on” the precepts of Christianity has clearly been a cause for celebration. Over and over again, academics, atheists, secular humanists, and popular magazine writers, among others, have trumpeted the Treaty of Tripoli as presenting conclusive proof that Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Franklin, and all of the other legendary characters who were there on the front lines in the early days of our Republic really were not much interested in religion, and that they were not motivated in their words and actions by any sort of deep religious feeling.

At first glance, this interpretation seems reasonable. But in historical study, one of the most basic, fundamental principles of the profession is that you should never, under any circumstances, try to interpret the deeds and motivations of historical actors from the perspective of the modern observer. In historical analysis, text is always superseded by context, by the reality of the specific historical moment being studied, and if this is not understood misinterpretation and misunderstanding are not just likely, they are inevitable.

The first thing to note is that Article XI does not actually say that the United States itself was not Christian at its core. What it says is the government was not in any sense founded on the Christian religion, and there is a difference here that is more than trivial. In our time, the federal government has grown so massive, omnipresent, and overbearing that the distinction between the country and the government has become obscured. Now, when someone says “the United States of America” it is basically taken for granted that the person in question is talking about the U.S. government, about its policies and actions both foreign and domestic.

But at the turn of the nineteenth century, things were quite different. The federal government at that time was restricted in both scope and responsibility, and when someone spoke of the United States government, they were talking about an organization with a specialized and limited role to play in the life of the country and of its citizens. So, for a document to state that the U.S. government was in no way founded on the Christian religion, this is simply pointing out what the First Amendment makes plain, namely that the new federal government had no reason to take any steps to establish an official religion, but would instead get out of the way so that the people were free to worship God in whatever way they saw fit. And in the early days of the Republic, there was little doubt that this freedom to worship for the most part meant the freedom to worship the Christian God, because everyone recognized that the United States was indeed, at her core, a Christian nation.

For those who doubt the truth of this statement, they need only read the words of John Adams, who as president actually signed the Treaty of Tripoli that had been negotiated by his predecessor’s envoys:

“The general principles on which the fathers achieved independence were…the general principles of Christianity…I will avow that I then believed, and now believe, that those general principles of Christianity are as eternal and immutable as the existence and attributes of God; and that those principles of liberty are as unalterable as human nature.”

These words, which were written in a letter Adams wrote to his friend and colleague Thomas Jefferson in 1813, make it clear how the founders saw themselves, their mission, and their fledgling nation.

While it is necessary to put the words of Article XI of the Treaty of Tripoli in its historical context as it relates to the United States, we must also consider the history of the Muslim peoples of North Africa. Motivated as they were by a sense of Muslim brotherhood, they were very well aware of the crimes and vendettas that had been carried out in the past against Muslim peoples by the “Christian” governments of Western Europe. The Crusades, the Inquisition, anti-Jewish pogroms, the annihilation of breakaway sects like the Cathars, and other similar actions came to be associated with Christian practice and belief in the minds of many – including the Barbary states of North Africa – because the European governments that had persecuted minorities and other vulnerable groups were quite explicit in the way they used Christianity to justify these campaigns, many of which included real atrocities.

All of this was well understood by the men who were sent across the sea by President Washington to negotiate the Treaty of Tripoli. They knew what Muslims had experienced in the past at the hands of so-called Christian nations, and their mission was to do everything they could to convince the Barbary States that the U.S. government, its elected leaders, and its citizens were cut from an entirely different cloth. The U.S. was a Christian nation, yes (this was a given, so it did not need to be stated directly), but unlike the nations of pre-Enlightenment Europe, it had not been founded on the Christian religion per se, and therefore had no intention of trying to punish infidels or spread Christian practice and belief by force.

When reading the opening line of Article XI of the Treaty of Tripoli, it is necessary to pay special attention to the second clause of the sentence, which demonstrates the truth of the preceding analysis:

“As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility of Musselmen [Muslims]…”

What was happening here is that the envoys who crafted the language of this treaty were trying to reassure the Barbary states that the U.S. had no hostile intentions toward non-believers, because we had embraced a version of Christianity that was tolerant of other faiths and had no interest in trying to destroy those who refused to convert to the one true religion. This is why Article XI contains the kind of language that it does, and anyone who tries to claim that the Treaty of Tripoli is somehow expressing a generalized indifference to Christianity among the founders of our country is committing the cardinal sin of interpreting history from a modern secular perspective.

The Importance of the Historical Method

At the time the Treaty of Tripoli was composed, it was well understood by everyone that the United States of America was and would continue to be a Christian nation. This was why the warring Barbary States included U.S. merchant ships on their list of legitimate targets, and it was why the U.S. felt it necessary to include language in the peace treaty they negotiated with those states that contextualized and clarified the role that Christianity played in American society. Ultimately, the Muslim states simply did not believe the U.S. government was telling them the truth about what their Christian heritage really represented, and this was one of the primary reasons why the Treaty of Tripoli failed to end hostilities. But at no point during this dispute was there ever any doubt in anyone’s mind that the United States was a member in good standing of the broader Christian community.

For the sake of accuracy and clarity, historical analysis must be conducted dispassionately and must not be used to promote an agenda. While those with a desire to spread the good word about religion have often been accused – and sometimes not without cause – of violating this standard, in the case of the Treaty of Tripoli it is those who wish to ignore the constructive role that religion has played in U.S. history who are guilty of this crime against logic and reason.

©2012 Off the Grid News

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living