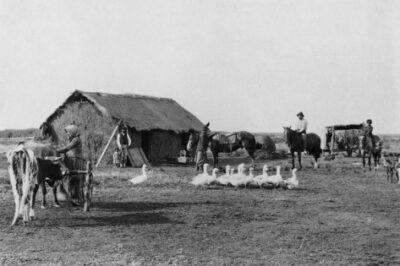

As the 20th century dawned, Argentina was among the 10 richest nations in the world and rivaled the United States as the great land of opportunity. So many immigrants were pouring in that in 1914 half the population of Buenos Aires was foreign-born![i] It was a land of milk and honey — or rather, beef and grain. Argentina exported crops and cattle from its rich fertile Pampas and had the 10th-largest trading economy in the world.[ii]

All that changed during the Great Depression, when foreign nations grew too poor to buy Argentina’s agricultural exports; as such, Argentina could no longer afford to import industrial goods. Thus began a policy of import substitution industrialization (ISI), in which the government aimed to reduce foreign dependency by encouraging the manufacture of Argentina’s own industrial goods. This was done by enacting tariffs, quota systems, and tax incentives to protect domestic industries from foreign competitors, with the idea that eventually these businesses would no longer need protection to compete.

Although ISI policies helped the South American country through the Depression, in the long run they crippled her economy. Instead of capitalizing on Argentina’s strengths—the lush, arable Pampas and the abundance of agricultural workers—protectionism artificially promoted industry and manufacturing, leading to inefficiency and lack of innovation. Domestic products didn’t have to compete with foreign ones, so there was little incentive to lower costs or to improve technologies. And Argentina has paid the price: once the 10th-largest trading economy, it had fallen to 33rd a hundred years later,[iii] with great income disparity and a standard of living that cannot honestly be described as first-world, despite an overabundance of natural resources.

By necessity, Argentines have learned to deal with national debt crises, inflation, and economic instability with resilience and ingenuity – and we can learn a lot from not only them but other “off-gridders” in other countries. They are, after all, quite resourceful.

Here are 12 lessons:

1. Maximize your skills. Non-importation means that the material goods sold in Argentina were actually produced there, too. Low-income families employ cottage industry to survive: assembling soccer balls or doing piecework sewing. Since some products, like electronics, are very expensive, machines and appliances are repaired dozens of times before they’re thrown out. Learn some new skills: Take advantage of all the free excellent YouTube tutorials to learn how to do a home repair yourself, or to teach yourself a new hobby or skill that can make you money.

2. Eat the whole chicken. From enchiladas to tikka masala, every recipe we make calls for boneless, skinless chicken breasts when in fact just about any part of the chicken will do. In Argentine supermarkets and pollerías, you can’t buy chicken breasts, or even drumsticks; chicken can only be purchased gutted, skinned, and whole. Next time you’re at the grocery store choking on the price of chicken breasts, throw American convention out the window and buy a whole chicken (much cheaper per pound) and learn how to use all the parts of it to cook up several delicious, frugal meals for your family.

3. Skip the packaging. In Argentina, eggs and produce are purchased from a local verdulería, where you carry everything home in your own shopping bag and wrap your eggs in sheets of newspaper to transport them without breaking. Instead of purchasing excessively packaged produce from Costco, buy it locally from your farmers’ market or CSA, and bring your own bag or basket to pack it in.

4. Eat fresh, local, and in season. Since Argentina imports hardly any produce, grocery choices are limited to what’s in season and being sold at the verdulería on the corner. That means no broccoli and cauliflower in the autumn, and no fresh tomatoes in the dead of winter; but then again, it means that every food is consumed in its optimal season, at the peak of its freshness and flavor, without having made a thousand-mile journey in a semi-truck. We’d be wise to follow suit and buy local produce in season.

5. Eggs don’t need to be refrigerated. Really, they don’t! Argentines never do. Eggs have a natural protective coating, called a bloom, which keeps germs and bacteria out. The bloom is blasted off with hot water and chemicals in egg processing plants; that’s why grocery store eggs must be refrigerated (not to mention that commercial egg and poultry farms are notorious for being filthy and salmonella-infested). But if you buy your eggs at your local farmers’ market, or get them from your own chickens, you can store up all the eggs your family needs for months and they won’t go bad (just make sure not to wash them until you’re ready to use them — use sandpaper or steel wool to rub off any debris).

6. Use chickens for pest control. If you raise chickens, chances are good that you let them out to forage in the yard every day. Chickens that eat weeds, seeds and insects have tastier, more protein-rich eggs. But have you ever thought about your chickens as free pest control? In Argentina, the combination of hot summers and irregular garbage collection means lots of cockroaches and pests. Many families combat this problem by letting their chickens roam the yard and forage all day. The chickens eat the cockroaches and the smaller insects that roaches feed on, thereby keeping their populations in check. It sure beats paying hundreds of dollars to hire someone to spray toxic chemicals all over your home.

World’s Smallest Solar Generator … Priced So Low Anyone Can Afford It!

7. Bundle up — even inside. You don’t need to keep your house at 70° F, or even 68° F, in the winter. The average Argentine home has cinderblock walls, a concrete or tile floor, and no insulation. Furnaces are non-existent; most people depend on radiators or space heaters to stay warm, and some houses have no heating at all. Dressing warmly isn’t just for going out; hats and jackets are worn all winter, even inside. Try it for a week; challenge your family to dress warmly and turn the thermostat down to 55° F or 60° F and watch your heating bill go down.

8. Cover your neck! If you’ve ever gone out on a cold day in Argentina without a turtleneck and scarf, you’ve undoubtedly been reprimanded by young and old alike. It’s the great Argentine secret for staying warm in the wintertime; everybody wears a turtleneck under their shirt every day, and scarves are layered up for insulation. Throw on a scarf and you’ll see how covering your throat actually makes a bigger difference than putting on a whole extra jacket.

9. Utilize bicycle transportation. Have you ever seen a soccer mom picking up two children from school on a bicycle? Or a painting contractor on his way to the jobsite toting an eight-foot ladder on one arm while he steers his bicycle with the other? In Argentina these are everyday sites (really!), since many can’t afford cars. Install a basket on your bike, and next time you need to grab a gallon of milk, ride to the local gas station or convenience store instead of driving your car to the supermarket.

10. Support your local economy. On every block in every neighborhood in Argentina, you’ll find a kiosco — a little convenience store set up in somebody’s front room. Maybe you don’t want to open a five-and-dime in your living room, but you can support your own community’s economy. Buy from small local businesses whenever you can. Hire a kid down the street to mow your lawn instead of a landscaping company from the neighboring city. If you have a bumper crop of zucchini, share some with your neighbors. Small acts like these build relationships and keep jobs and money in your community (which means better job security for you, too).

11. Clothes dryer? What’s that? In Argentina, virtually nobody has a clothes dryer. You can significantly lower your electric bill by drying everything on a rack or clothesline.

12. Wash your laundry in a bucket. Since only about half of families can afford a washing machine, hand washing is an essential skill. Establish a household rule to never run the washer for a very small load such as three items or less. Get proficient at sink-washing clothes, and teach your kids to do the same.

What practical skills and off-the-grid living strategies have you learned by living abroad? How have you applied these skills in your life back at home? Share your thoughts in the section below:

[i] The Economist. “A Century of Decline.” <https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21596582-one-hundred-years-ago-argentina-was-future-what-went-wrong-century-decline>, February 15th, 2014, accessed January 2015.

[ii] Rick Lovering, “An Interpretation of Argentine Economic and Political History: Dutch Disease on the Pampas”, page 2, <https://kb.osu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/1811/28514/Full_thesis.pdf>, accessed January 2015.

[iii] Lovering, page 2.

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living

Off The Grid News Better Ideas For Off The Grid Living